While the OECD forecasts the Pillar Two measures will raise $US220 billion ($330 billion), the expected tax take in Australia is relatively modest, says Deloitte tax partner David Watkins.

“It is hoped that the Australian approach to design and compliance is commensurate with the forecast tax revenues,” Mr Watkins said.

Australian subsidiary

Treasury says it will raise $160 million from the new taxes in fiscal 2026 and $210 million in 2027, but the lengthy period of companies filing tax returns in multiple countries, the process of tracing where Australian profits go, and finally extracting payments cast doubt on the timing of any payments.

The Pillar Two system aims to make sure all companies pay at least 15 per cent tax. But do not expect that to be in Australia.

As an example, a US tech company sells products or services through an Australian subsidiary which pays tax here on Australian income. That taxable income is low because the Australian subsidiary pays licensing fees to an associated company in Singapore, which pays 5 per cent tax on a slice of the funds but sends most of the licensing fees to tax-free Bermuda. Or Ireland.

If the US parent ends up paying less than 15 per cent tax over all its sales, then under Pillar Two Australia could charge a top-up tax to the Australian subsidiary, to ensure the overall tax rate is 15 per cent. But Singapore might want to do that as well, charging a top-up tax on the same funds, which makes the process cumbersome, time-consuming and a lawyer’s delight.

Then there is the US. It is expected to refuse to sign up for Pillar Two, which will send the whole tax reform process into deep freeze.

Australia’s track record for cracking down on multinational taxpayers is modest. The centrepiece of this effort last decade, the 2016 multinational anti-avoidance law (MAAL), targeted 44 companies and raised just $100 million in the income tax year, second commissioner Jeremy Hirschhorn told Senate Estimates in February. It also raised $80 million of net GST.

In 2014, at the start of the reform process, firms like Apple, Alphabet-Google, Microsoft and Facebook were being audited by the ATO amid widespread concern that the four firms were making huge profits from Australian clients on which little to no tax was paid in Bermuda, Ireland and elsewhere.

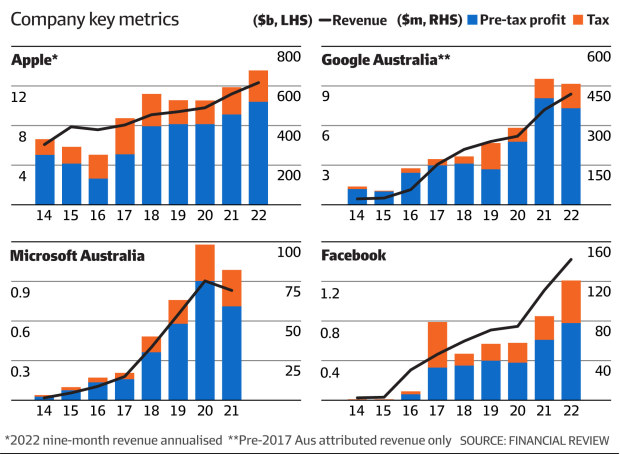

What corporate filings show is that tax payments jumped around 2018 as firms made tax settlements after ATO audits covering multiple years, but once that effect passed, the tax increase was relatively minor.

In the past 10 years Australians have paid $84 billion for Apple products. Apple reported $3 billion taxable income during that time and paid $1.17 billion in Australian tax.

Apple’s 2022 results were for just nine months. “Normalising” that up to a full year, it is equivalent to $12.4 billion of sales, $521 million pre-tax income and $159 million tax. Apple Inc’s global gross margin was 43.3 per cent last year, so on an annualised basis its Australian gross profit was more than $5 billion, and the ATO got 3 per cent of that.

Comparisons over time

It is more complicated than that. But compare 2014, before the MAAL, the diverted profits tax and other measures, when Apple’s Australian sales were $6.1 billion, its pre-tax profit $252 million and its tax $80 million.

Apple’s sales have doubled since then and so has the tax it pays here. So what has the past decade achieved? Apple’s global effective tax rate has dropped from above 25 per cent to hover now around 15 per cent – high enough that it won’t be troubled by Pillar Two.

It does not work to compare sales directly with income tax. But it is telling to compare these high margin firms over time.

Elsewhere, Facebook Australia has gone from paying $681,000 tax in 2014 on $26 million revenue to $33.7 million last year (excluding previous years’ adjustments) on sales of $1.4 billion.

Similarly, Microsoft Australia’s tax went from $439,000 in 2014 to $23.2 million.

The change is most pronounced at Google Australia, where tax went from $9.5 million in 2014 to $92.6 million last year, as Australian revenue rose from $438.7 million to $1.95 billion (another $6.5 billion booked offshore is not taxable here).

The true total for what Apple, Google, Facebook and Microsoft extracted from Australia in 2022 is probably more than $25 billion, less costs, on which they paid $317 million tax.

If they are concerned about Pillar Two, they have a terrific poker face.