Tesla Inc.’s Model 3 contained 4.5 kilograms of cobalt in its power pack in 2018, materials analyst Benchmark Minerals Intelligence estimated at the time. Scale that up to the 7.8 million electric vehicles sold last year — 10% of the global market — and then project forward into a future where that share rises toward 100%, and you can quickly see the world running into a supply problem.

Sure enough, prices for lithium-ion batteries rose last year for the first time since at least 2010 as materials pushed up the price, according to BloombergNEF. You would hardly be surprised if things got worse as green investments in the US, European Union and China ramp up over the coming years.

The metals demand from the energy transition “may top current global supply,” the International Monetary Fund warned in a 2021 analysis. Difficulty securing materials such as lithium, cobalt, tellurium and copper could hamper the shift to cleaner energy, Imperial College London’s Energy Futures Lab wrote in December.

Bloomberg

BloombergNew data from the US Geological Survey show why some of those fears are likely to be overblown. Each year, the USGS analyses almost every commodity on earth, from iron ore to indium and palladium to peat, to get a handle on whether production is sufficient to meet the world’s — and in particular, America’s — needs.

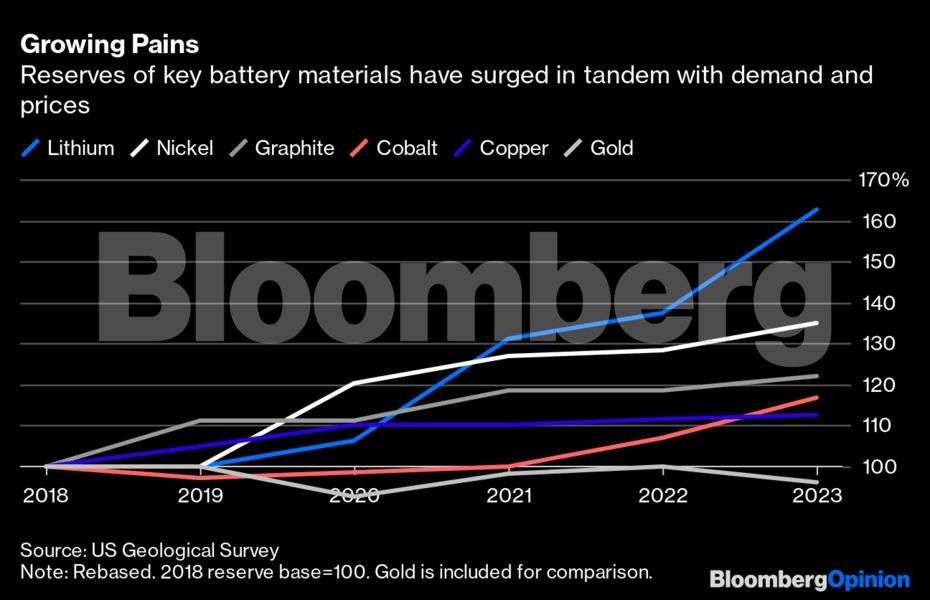

The latest figures show a boom in supplies of many of the most important minerals for the energy transition. Lithium reserves are up 18% from last year. Cobalt has seen a 9.2% gain. Rare earths, which have a range of high-tech applications including magnets in electric car motors and wind turbines, saw reserves up 8.3% after standing still for at least five years.

Part of this is a mathematical result of the rising prices that pushed lithium carbonate to nearly $80 a kilogram ($36 a pound) last year, from a range of $10/kg to $20/kg previously. “Reserves” measure minerals that can be profitably mined, so when price expectations increase, the reserve base will grow as well. Mostly, however, it comes from miners going out and doing what miners do when the market prices of their commodities go through the roof: Dusting off old geological results and drilling rock to find new deposits.

This process is aided by the sums of money that have flowed into battery materials in recent years as fears of supply tightness have grown. The small volumes involved in elements such as lithium, cobalt, and battery-grade nickel have meant that major mining companies tended to ignore them to focus on the vast cashflows that can be generated from iron ore, copper, aluminium and (until recently) coal.

Bloomberg

BloombergAutomotive companies, which have most to lose from a supply shortfall, have stepped in, too. General Motors Co. last week invested $650 million in Lithium Americas Corp., which hopes to produce 80,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate from a mine in Nevada — equivalent to more than 10% of global production last year. Tesla, meanwhile, has reconfigured its batteries so that half of its cars contain no cobalt or nickel at all, helping to shave demand even as supply increases. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. argued last year that the battery materials boom had already peaked, with huge supply investments likely to push prices into a slump until the second half of this decade.

The same goes for the effect of all these materials on another non-renewable resource — the atmosphere’s carrying capacity for carbon dioxide emissions. Building all the power sector infrastructure needed to give the world a two-thirds chance of keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius would use up between 1% and 9% of the world’s carbon budget, according to a study in the science journal Joule last month by researchers led by Seaver Wang of the Breakthrough Institute, a climate-related US think tank. In 84% of the scenarios the researchers examined, all the wind turbines, cement foundations, solar panels and steel frames installed up to 2050 would use up about six months’ worth of current emissions, while decarbonising a sector that accounts for as much as 40% of our annual carbon pollution.

In that, the market for transition materials is just repeating a pattern that’s held since the Biblical Pharaoh dreamed of seven years of plenty turning to seven years of famine. Fears of catastrophic shortfalls aren’t so much a prophecy of doom, as a corrective that ensures the right investments are made to guarantee supply always meets demand. Even a once-in-history switch to low-carbon power won’t be enough to break that eternal rule.