When it comes to music, I’m ashamed to say I’m a bit of a philistine.

Only in the indifference sense, not hostility. Don’t get me wrong, I like music, and can certainly fall into the trap of playing a new song over and over.

But I can also go for days without listening to music and don’t miss it.

With that in mind, I was intrigued when invited to join the Brainstorms Project, a collaboration between Pollen Audio Group and Dolby to record the brain activity of 100 volunteers while listening to Pink Floyd’s The Great Gig In The Sky.

Full disclosure: I’d never heard it before. That’s the level of musical ignorance we’re talking.

Nevertheless, I was excited to visit Dolby’s Soho HQ and find out what exactly was going on in my brain. Hopefully something.

Entering one of Dolby’s subterranean studios, I meet neuroscientist Erica Warp, charged with recording the billions of brainwaves from all 100 volunteers.

Despite the mammoth task she is incredibly cheery, running through what would happen while fitting the headset designed to peek inside my skull. It had a hint of Meccano about it, a spidery web of black.

After dabbing the electrodes with saline – for conductivity, not post-Covid hygiene – Erica rolls the headset in place (I wasn’t expecting a free head massage too).

As I get used to the feeling, she reels off instructions: face the speakers, try to clear your mind, and if I have a ‘chill event’ – a shiver or similar reaction – to press a button she hands me.

‘Most people become more stressed when listening to the instructions than the song,’ she jokes.

Kitted out, I swivel around to face a row of speakers, each with a round silver diaphragm, staring back at me like a little row of Minions.

I’m not sure what to expect as the first notes blast out, but it certainly isn’t this. The opening piano chords and guitar riffs, overlaid with a chap chatting away (who I later learn is Gerry O’Driscoll, a janitor at Abbey Road Studios), are very mellow.

What follows isn’t, and, I’ll be honest, is a tad confusing.

While the famously ‘orgasmic’ screams of Clare Torry are impressive in their range and an unexpected element, I find myself simply waiting for the real lyrics to start. Which of course they never do.

Of course, there is no doubting the quality of the sound pulsing through the speakers, but that too is sadly lost on me – I will quite happily blast tinny music out my phone at home, much to others’ disgust.

After almost five minutes, the song is over, and so too is my brain scanning time.

Obviously I can’t resist a ‘so do I have a brain’ joke, which Erica graciously smiles at, having no doubt heard it another 99 times over the week.

But I do have a brain. And it does not care about Pink Floyd.

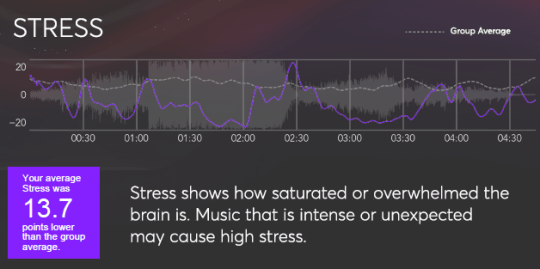

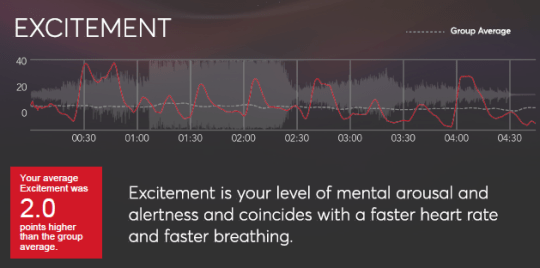

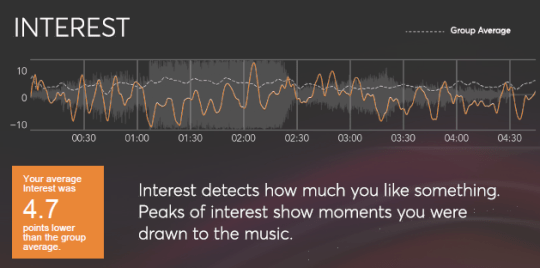

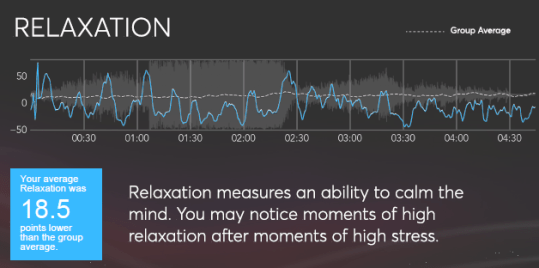

Four measures of brian activity were taken – interest, relaxation, stress and excitement.

Peaks of interest showed where participants were drawn to the music, relaxation measured the ability to calm the mind. Stress, well, you know, and excitement measured mental arousal and alertness.

Overall, my interest in the music was 4.7 points lower than the group average, although strangely my excitement was two points higher.

In another contradiction, my relaxation was 18.5 points lower than average, but conversely my stress was also lower than average, by 13.7 points.

And while I experienced no ‘chill’ events, my stress often spiked when others had them. Perhaps Pink Floyd just isn’t for me?

Let’s not be too hasty.

Psychology professor Joydeep Bhattacharya, from Goldsmiths University warns against making sweeping judgements, especially without any baseline levels to compare them too.

If I had to hazard a guess, I’d say I’m pretty stressed and not very relaxed a lot of the time.

In addition, the results were influenced by many factors long before I stepped in the studio, simply from me being me. For instance, low interest doesn’t necessarily mean I don’t like the music, it could suggest a more contemplative engagement.

I’m not so sure on that, I don’t recall much contemplation, other than wondering when the lyrics were going to start.

But most importantly, EEG signals are a wide and complex set of signals, coming from different areas of the brain, but these weren’t defined in the results.

Professor Bhattacharya says: ‘While the results show how Katherine might have felt – like stress or excitement – during listening, it’s important to remember that everyone’s reaction to music is different and even the same individual responds to music differently, depending on context.

‘In short, while this experiment gives us a cool glimpse into how music can affect our brains, there’s a lot more to explore about how each of us uniquely experiences music.’

It is cool, even if not the most scientific of experiments, and it gets even more so when the final stage is revealed.

The team has taken my brainwaves and transformed those thoughts and feelings into a mesmerising cloudscape.

‘The visualisation, built in Unreal, a 2D fly-through of the cloud system – but the behaviour of the clouds and how they look is being controlled by the brain data,’ says Richard Warp, Pollen’s creative director.

‘Flashes are interest spikes, foggy diffuse effect is relaxation. The density of the clouds, how many there are, is being controlled by excitement.’

It’s a hypnotic combination, easy to get lost in. Admittedly there are a few lulls, perhaps unsurprising given my apparent middling feelings for the poor Clare’s genre-bending vocals.

Still, I can’t help but wonder how my brain would react this time, listening and watching simultaneously.

And had I known before that The Great Gig In The Sky was about death, that too may have changed my experience.

Alas, I’ll never know, but the project did remind me of the simple joys of switching off and immersing yourself in music.

Even with a web of Meccano on your head.

MORE : Mind-reading AI recreates Pink Floyd classic from listener’s thoughts

MORE : First ever recording of moment someone dies reveals what our last thoughts may be

MORE : This is what happens to your brain when you use social media in the morning

Get your need-to-know

latest news, feel-good stories, analysis and more

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.