The need to feed an expanding population while cutting agriculture’s high greenhouse gas emissions means farming must become more efficient. The increased use of genetic technology in seed manufacture is one solution. Yet GMOs remain a bugbear for many ESG funds, which are wary of the unintended consequences of intervening in the food chain (the so-called precautionary principle).

The difficulty with this cautious position is that it becomes harder to maintain if it exacerbates the risk of a food crisis. And so some investors are now betting that ESG sentiment will shift.

Agriculture’s environmental impact cannot be ignored. The activity is responsible for roughly a quarter of global emissions, according to the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Deforestation for cropland damages biodiversity, and there’s a continuing need to reduce the toxicity of pesticides and herbicides.

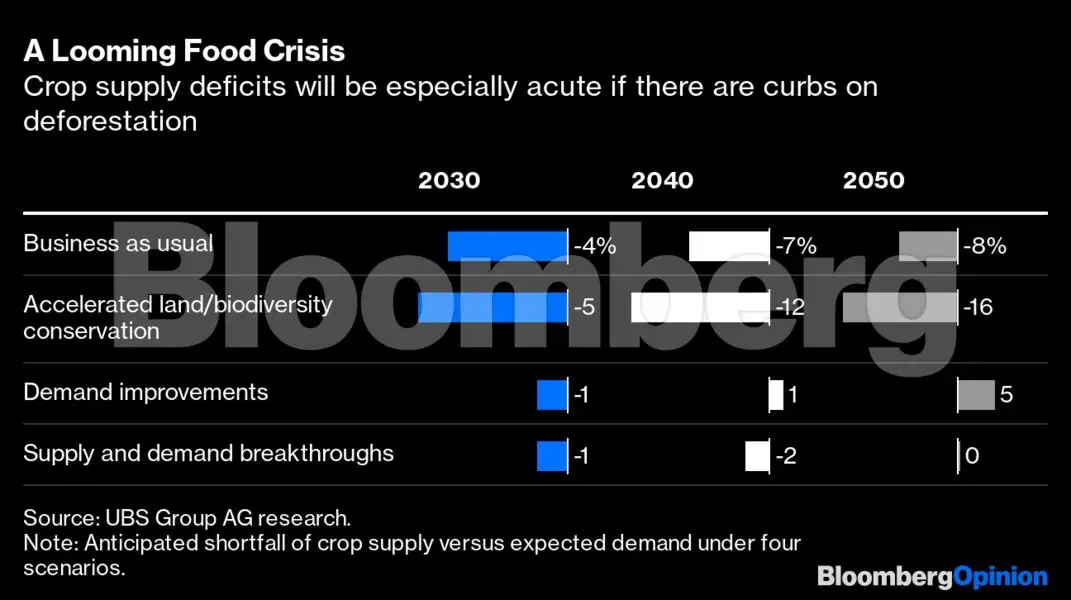

Countering this, however, is a stark social consideration. Global crop demand is on course to be 61% higher in 2050 versus 2020, according to analysts at UBS Group AG. While crop yields have been improving, these gains would need to accelerate to prevent a shortfall in crop supplies possibly as soon as the turn of the decade, UBS reckons. Without such improvements, the research finds, the additional cropland needed to meet demand is equivalent to the combined land area of the UK, France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Might the problem be solved by changing dietary habits, reducing the need for certain crops, or cutting food waste? UBS considers a scenario where consumers in higher-income countries eat less meat, the population grows at the lower end of UN estimates and there is a reduction in both food waste and biofuels usage. There’d be enough crop supply, but no reforestation. So efforts to promote biodiversity would suffer.

Bloomberg

BloombergThis means meeting both environmental and social goals will require solutions that tackle supply and demand together. Industries delivering these could make $1.3 trillion of annual revenue by 2050, UBS predicts. Chief among them are seeds and plant genetics, given their potential to boost crop yields.

The direct investment opportunities, though, are scarce. Two listed companies — Bayer AG, the German life sciences group that bought controversial genetically modified seeds pioneer Monsanto in 2018, and Corteva Inc., spun out of the merger of Dow Chemical and Dupont in 2019 — dominate the seeds industry. ChemChina’s Syngenta, the number three, is mulling a listing but the timing is unclear.

Bloomberg

BloombergWhich brings us to the recent arrival of activist funds in Bayer, including the social-impact-focused Inclusive Capital Partners LP, established by Jeff Ubben, the founder of investment firm ValueAct Capital.

Activists seek stocks trading below perceived fair value, with identifiable catalysts to close the gap. Bayer’s market valuation suffers a sizeable discount to Corteva, even allowing for the fact that half its business is in pharmaceuticals. The obvious triggers to close the discount are: a decisive settlement of litigation claiming that herbicides containing glyphosate cause cancer; management change; and listing a stake in the crop-science business to attract investors deterred by Bayer’s conglomerate structure.

But in addition to these conventional value drivers, there’s the possibility that attitudes in ESG toward the crop-science sector radically shift. For some ESG funds and indices, companies that make more than a fraction of their revenue from genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are off-limits as much as companies involved in tobacco, gambling and nuclear weapons. The question is whether sentiment globally will move toward viewing genetic technology in food as necessary to achieving decarbonisation, which would in turn feed into higher ESG scores.

Bloomberg

BloombergOutside the US, the world has so far been hesitant to accept GMOs in the food chain. But the evidence to support the investment thesis is gathering.

Emissions from food production are becoming part of the corporate and investor conversation. French dairy giant Danone SA said last month it was targeting a 30% reduction in methane emissions from its fresh-milk supply chain by 2030. Others will come under pressure to make similar commitments. Index provider MSCI Inc. modified its ESG exclusion criteria last year, with the result that companies involved in GMOs may now be less likely to attract a red flag. Analysts also point to so-called gene editing being potentially more acceptable to the public and regulators than genetic modification, as GE involves altering a plant’s DNA without introducing a foreign gene, as in GMOs.

Financial markets can help by allocating capital to the companies best placed to prevent a food crisis. But the G leg of the ESG stool will also take on critical importance too. The need for large R&D budgets means crop science is likely to remain concentrated around a small number of powerful players. Good governance will be crucial. A limited number of seed manufacturers, who may be cross-selling fertilisers and crop protection chemicals to the same customers, is hardly ideal (not least considering the need for biodiversity).

This industry needs not just activists, but active, long-term investors who will bring the best scrutiny the public markets have to offer.