Corn output from agricultural powerhouse Brazil is surging, making it more profitable to use the grain to produce ethanol — a key fuel that powers cars in Latin America’s biggest economy. As a result, mills that crush costlier cane are looking to produce more sugar and less biofuel.

“Anyone with money today is either investing in corn ethanol, or adding capacity to produce sugar,” said Eder Vieito, senior commodity analyst at Green Pool Commodity Specialists.

Falling sugar prices would be a welcome respite for consumers battling rampant food inflation. A gauge of agricultural commodity prices posted its biggest gain in 16 months in July, before retreating somewhat in August. Extreme weather has damaged sugarcane in India, the world’s second-largest producer after Brazil.

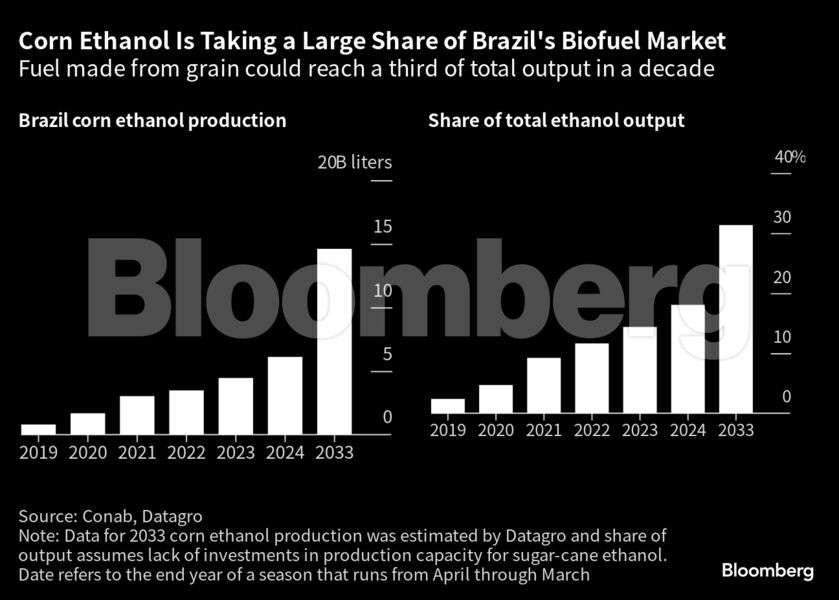

Corn is taking a bigger share of the ethanol market in Brazil, which trails only the US among global producers of the biofuel. Ethanol from corn will account for nearly a fifth of all output of the fuel this season, from nearly zero five years ago. By 2033, its share could climb to as much as a third of total supply, consultancy Datagro predicts.

Bloomberg

Bloomberg“Biofuel expansion will predominantly come from corn,” said Renato Pretti, strategic planning officer at ethanol producer Cerradinho Bioenergia SA. The company, which uses both corn and sugarcane as raw material for fuel, is one of a growing number of mills diverting more cane to produce sugar and even investing in new sugar machinery.

Rising corn output in Brazil is allowing for bigger profits from ethanol as sales of byproducts like animal feed mostly cover the cost of the grain. Cane mills, in contrast, recently saw shrinking margins from producing ethanol. The cost of making ethanol from corn was 16% lower versus producing the biofuel from sugarcane over the past two years, analysts at bank BTG Pactual said in a report.

Bloomberg

BloombergEthanol demand, however, has been lagging as drivers embrace cheaper gasoline. Prices for the biofuel could drop to as low as 65% to 68% of the price of gasoline in the long term, according to Willian Hernandes, a partner at consultancy FG/A. A drop below 70% will convince more drivers to switch to ethanol, but it will also limit millers’ profits from making the biofuel. Cane mills have already made plans to add roughly 2.5 million tons of capacity to produce sugar in the coming seasons, FG/A estimated. Mills will probably keep maximising sugar production for at least two more seasons, said Murilo Mello, head of sugar for the Americas at Hedgepoint Global Markets.

Bloomberg

BloombergThe sugar industry’s deep political ties in Brazil may ultimately help to boost its ethanol margins, however. The government of president Lula da Silva is supporting a bill that will increase the percentage of ethanol mixed with gasoline.

Corn-based ethanol also faces some hurdles. Mills that use the grain rely mostly on biomass from wood chips as a source of energy, and wood supplies are tightening in Brazil amid growing pulp and paper production. That could mean less incentive to grow corn ethanol supply beyond what’s already planned, said Ana Zancaner, an analyst at Czapp, which is owned by commodities trader Czarnikow Group Ltd.

But the consensus is that corn ethanol will have a few more years of expansion. Brazil has eight corn ethanol plants adding capacity, while other seven new mills are under construction, analysts at Itau BBA wrote in a September report. Supply of the raw material is also abundant: the analysts estimate Brazil will consume a record 13 million tons of corn for ethanol this season, about one-tenth of total supplies.

That’s good news for corn producers in the top growing state of Mato Grosso. There’s significant potential for the grain to grab a bigger share of the ethanol market, according to farmer Zilto Donadello.

“Corn ethanol still has a lot of ground to cover,” Donadello said.