Good morning. Two years ago the government pledged to axe Britain’s 200-year-old Vagrancy Act, under which thousands of homeless people have been arrested. A “suite of modern enforcement powers” via the Criminal Justice Bill will replace it, so said the Conservatives, who also pledged to end rough sleeping by 2024.

Well, such is the march of progress that these new measures to fine, move on or jail “nuisance” rough sleepers have been labelled even worse than the Vagrancy Act by the chief of charity Crisis and, er, at least one Tory MP. It’s also a distraction from the evidence.

Inside Politics is edited by Darren Dodd today. Read the previous edition of the newsletter here. Please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to insidepolitics@ft.com

Connecting the dots

I had to take two buses to get to secondary school. One from my street in Milton Keynes to the train station, and then another 40-minute one from there to the next town, Buckingham. Clusters of homeless people inhabited the underpass by the station. Every day, as I waited there for my bus, I witnessed gradually more tents pitching up. One day, a man named Jimmy Owen was found dead in his tent in the underpass.

A year after that, former FT reporter Naomi Rovnick visited the station and chronicled the spiralling situation in Milton Keynes, which had one of the worst rates of youth homelessness nationwide and was widely dubbed “tent city”. It’s a hard-hitting piece:

Mark says he had been living in a room in a shared house for £67 a week but “got chucked out when the landlord said he didn’t want housing benefit people any more”. Mark blames his problems on the rollout of universal credit, the welfare system that merges several benefits into a single payment and has ended the practice of housing benefit being paid direct to landlords.

Mark’s point is backed by much social science evidence showing that changes to universal credit and housing benefit had a direct causal impact on homelessness (Tom O’Grady’s recent book brilliantly documents the backdrop). We saw higher levels of rent arrears, while the stepping-up of sanctions, which disproportionately affected vulnerable UC claimants such as those with disabilities or poor IT skills, came at huge detriment to people’s financial and mental wellbeing.

Austerity and reduced social housing have left many at the mercy of the private rental market and possible eviction (by 2017, 71 per cent of Milton Keynes’ council homes had been sold to private landlords under right to buy).

As a result, stretched councils face ever tougher decisions on who to house, and where. A record 109,000 households in England were living in temporary accommodation between July and September last year, according to official statistics. These are people whose landlords have sold up, whose families have broken down, or have fled domestic violence. The Home Office’s rush to clear hotels of asylum seekers has compounded the rise in rough sleeping, as newly granted refugees are forced to find homes quickly or face the streets.

I called a few homeless charities and they all highlighted the structural problem: scant affordable housing. I talked to a support worker at Kingdom Way Trust (KWT) in Eastbourne who had just gone to view a private rental — as potential housing for their clients — near the coastal town:

The agent said it was £920 a month for an en suite room in a shared house. The LHA rate for that area is £430. So that’s nearly £500 a month that someone is supposed to find, plus bills.

One surprisingly good thing the government should be highlighting is the end to the freeze in local housing allowance (LHA) rates from this month. But despite the success of its pandemic initiative Everyone In, which temporarily housed 90 per cent of England’s rough sleepers and provided charities greater opportunity to help with complex needs, the government is yet to grasp the nettle on prevention. Its own “Housing First” pilots make the most powerful case for doing so.

With reportedly more than 40 Tory MPs suggesting they’ll vote against the Criminal Justice Bill, many parliamentarians recognise the scale of what’s needed — though some hold Suella Braverman-like attitudes on homelessness as a “lifestyle choice”. Still, homelessness occupies tricky territory that seems to be unlinked to broader housing affordability issues, and where ministers are visibly uncomfortable addressing its roots.

Part of that might stem from public perception. The headline stats from an Ipsos/Centre for Homelessness study repeated across three years from 2020 to 2022 are pretty consistent (the 86 per cent proportion who deem it a “serious problem” has barely budged in that time). But one noteworthy change was the second consecutive decline in the share of people who believe “decisions about homelessness should be made based mostly on evidence of what works” (57 per cent in 2022, down from 61 per cent and 65 per cent in the two previous years).

People also massively overestimate how many homeless people have an alcohol or drugs dependency — the average estimate was 53 per cent; the real figures are between 5 and 7 per cent. They overestimate the role of immigration.

The share of people who support an increase in housing-related benefits to help people afford somewhere to live has dropped from 66 per cent in 2020 to 59 per cent in 2022. All this is to say that I think homelessness — which affects a relatively small fraction of the population — is unlikely to be an election issue and risks cleaving further from “evidence”.

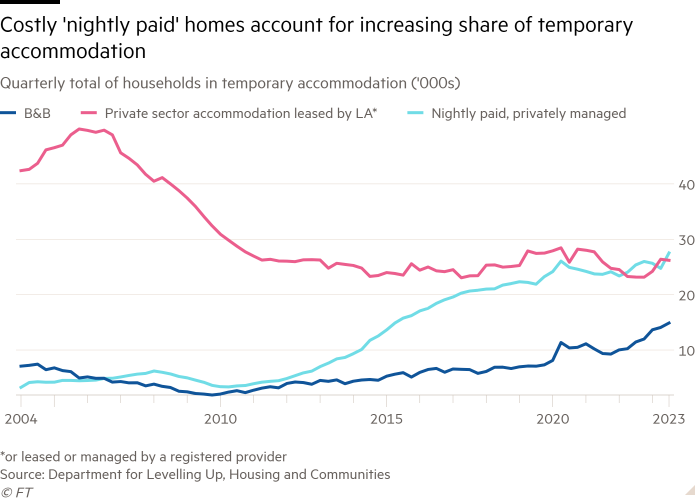

But given the outlandish expense of temporary accommodation, where some people can stay for years and high-cost nightly providers are “capitalising on the crisis”, perceptions could change.

Eastbourne, which has one of England’s highest rates of deaths of despair, is a pressing example: 49p from every £1 of the council’s existing budget is being spent on temporary accommodation. Many councils are in a similar position, spending huge sums because they must call on capacity that should (in a functioning system) only be used in emergencies. The amount spent on hostels and B&Bs alone totalled £565mn in 2022-23.

So what to do? Finland has shown that a “Housing First” model — under which “housing is the prerequisite that allows other problems to be solved” — is an important part of a long-term strategy. After Everyone In ended, KWT stuck to providing single-room accommodation instead of using communal night shelters, because that was so much more effective for tackling underlying issues and laying the foundations to help people sustain tenancies.

In Hastings, where one in 79 people are homeless (compared with one in 182 in England), a support centre combines housing help with classes for improving literacy, drawing etc. “The venue hosts statutory agencies such as jobcentres which normally would find the homeless difficult to reach,” says Trudy Hampton, head of the charity Warming up the Homeless, which supports 1,400 people a week in Hastings and Eastbourne. “Because they are at our premises, those walls have been broken down.” She called it a “one-stop shop” and “the future” of homelessness support.

Milton Keynes Council has improved its rough sleeping crisis this way, transforming an old bus station into a shelter that combines statutory and voluntary services.

The evidence is there: more social housing, long-term funding for support services, a cross-governmental approach, ending unhelpful criminalisation. The challenge for future administrations will be harnessing the existing political will to end homelessness, and honestly confronting the causes, rather than reacting to the consequences.

Now try this

I fervently dislike being near to my phone, nay, phones in general. “Which time gets killed when the smartphone kills time?”

Top stories today

-

Retire the rhetoric | The Conservatives should eschew “posturing” in favour of delivery to have any chance of holding on to power at the general election, according to Andy Street, one of the party’s most high-profile regional mayors.

-

‘It’s not Barbieland’ | Yolande Makolo, an aide to Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s president who visited Downing Street this month, said her country stood ready to accept asylum seekers whenever they arrived. But as the parliamentary “ping pong” nears completion, critics are warning they will not find the “good life they are looking for”.

-

Met sorry for broken promise to Baroness Lawrence | The Met Police has apologised to Stephen Lawrence’s mother for breaking a promise to answer questions raised by a BBC investigation into his murder. Baroness Doreen Lawrence was promised an explanation relating to a major suspect which the BBC publicly identified as Matthew White last June.

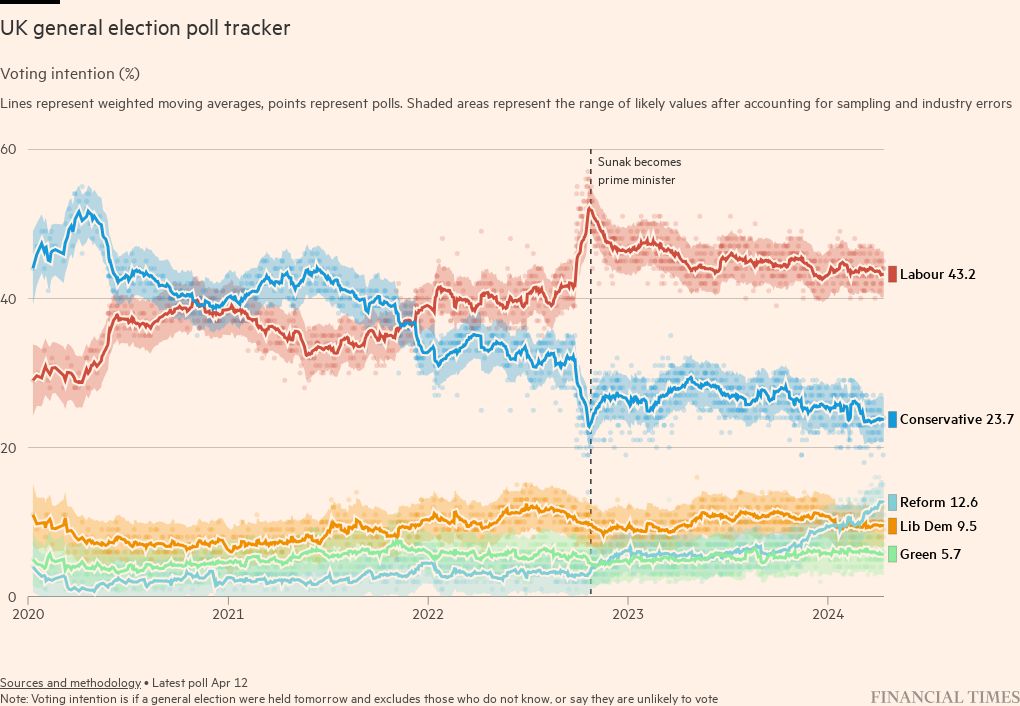

Below is the Financial Times’ live-updating UK poll-of-polls, which combines voting intention surveys published by major British pollsters. Visit the FT poll-tracker page to discover our methodology and explore polling data by demographic including age, gender, region and more.