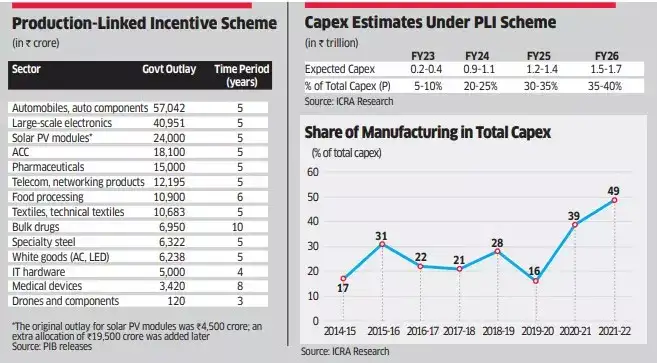

The PLI scheme — which offers incentives on incremental sales of products manufactured in India — was initially rolled out for three sectors in early 2020 and then extended to 11 more. The sectors covered under the government’s `1.97 trillion package include automobiles and auto components, electronics, solar modules, pharmaceuticals, telecom, food products, textiles, white goods and specialty steel. Capital expenditure (capex) is already being deployed in electronics, engineering goods and food products, with the recent surge in mobile phone exports being one of the discernible outcomes.

With the PLI scheme in place, the annual investment in India’s manufacturing sector may remain high for a few years from FY2023-24. But questions remain on whether the global economic uncertainty will delay the execution of projects and mess up the government’s math on private investments.

According to a recent analysis by credit rating agency ICRA, the deployment of capex may kick in in a big way in the next fiscal year of 2023-24, with investments likely to cross the `1 lakh crore threshold, and may touch `1.7 lakh crore in FY26. “Hence, FY24 could be an inflection point for a surge in India’s manufacturing capex,” says ICRA’s report published in November 2022. If announcements of new manufacturing projects are factored in, manufacturing’s share of total capex was 49% in 2021-22, up from 16% in pre-Covid 2019-20, according to the report. In 2015-16, manufacturing had a 31% share in India’s total capex before slipping in subsequent years.

So it is very likely that FM may put the spotlight on the PLI scheme in the upcoming budget and possibly package it as India’s Covid-time success story of Aatmanirbharta (self-reliance). Thanks to the liberal incentives under the PLI, the private sector, which has been otherwise reluctant to spend, has started investing some amount in new manufacturing facilities.

The likelihood of recession in some advanced economies is a huge concern. Officials in multiple ministries say on the condition of anonymity that capex deployment in some big PLI projects may get delayed due to global gloom. One-third of the world’s economies is projected to be slipping into recession in 2023. Kristalina Georgieva, MD of the International Monetary Fund, said in a recent interview to CBS that half of Europe could be in recession this calendar year.

ET Online

ET OnlineCAPITAL IDEA

Deepak Bagla, CEO of government owned Invest India, however, says capital can’t sit idle for too long. “Company results in India have been robust. Once this wait-and-watch phase is over, investments will come in very quickly,” he says. According to him, companies are on the wait mode for two reasons — one, lower capacity utilisation and, two, rising cost of setting up a greenfield project because of global supply-side disruptions. In terms of volume, the success of the PLI scheme will depend on how quickly investments pour into automobiles and auto components, electronics and solar modules — three sectors that get the lion’s share of the government’s proposed outlay under PLI.

Pawan Kumar Goenka, former MD of Mahindra & Mahindra and chairman of IN-SPACe, says PLI schemes for sectors such as automotive, advanced chemistry cells (ACC), air conditioning, mobile phones etc., have been hugely successful and are oversubscribed. “The government may consider increasing the outlay for oversubscribed sectors and bring in some new sectors into the scheme,” says Goenka.

What should happen if the outlay in some sectors remains unused because of lack of interest from stakeholders? “The outlay from the unused portion of existing schemes should be diverted to new sectors,” says a CEO, requesting anonymity.

However, Randheer Singh, director of electric mobility and senior team member of ACC programme in NITI Aayog, says the question of slowdown in investment in certain segments does not arise. “I don’t think climate transition investments will dry up. Globally, several countries such as the US are focusing on creating value chains on clean solutions. And these are long-term investments,” says Singh, pointing to some facts — one, PLI in ACC got oversubscribed 2.6 times; two, auto PLI has seen participants from across the globe; and three, the government has decided to provide `19,500 crore more to solar photovoltaic (PV) modules. All these are in the climate transition investments category.

The incentives offered under the PLI scheme are not uniform for all sectors. Nor is the period for which the government earmarks the fund the same. For instance, the incentive for a manufacturer of drones and drone components is 20% of the value addition made by the company. Meanwhile, for large-scale electronics manufacturing — one of the early PLIs notified in April 2020 that mainly targets manufacturing of mobile phones — incentives range from 4% to 6% on incremental sales over a base year, for a period of five years. For specialty steel, the incentive range is 5-15%. The PLI is usually given for five years with a few exceptions such as eight years for medical devices and 10 years for bulk drugs and active pharma ingredients, etc.

Once a company is selected under the PLI scheme, it is informed of the amount it will receive. For instance, Taiwanese multinational Foxconn Hon Hai Technology, which recently got PLI approval under the mobile phones segment, will receive `357 crore. Global companies have been selected for the PLI scheme, including Samsung and Taipei-headquartered Wistron, which is a contract manufacturer of Apple.

A company can be eligible for multiple PLIs. Noida-based electronic manufacturing services (EMS) company, Dixon Technologies, for example, has qualified for PLI in mobile phones, IT hardware and LED lighting (white goods) segments. Its executive chairman Sunil Vachani says the results are showing. “We made large-scale investments in mobile manufacturing in the past one and half years. Our exports have grown 500%. We are also building a facility for mobile phones, spread across 1 billion square feet, which would not have been possible without the PLI push,” he says. PLI schemes have reduced import dependence, encouraged localisation and added value in the auto component segment, says Sunjay Kapur, chairman of Gurugram-based Sona Comstar, which has manufacturing facilities in US, Mexico and China as well. He adds that the combined investment of 67 auto component companies under the PLI scheme could well be over `18,000 crore.

“Component manufacturers will lead the growth by investing in newer capabilities to supply to the globe and also help India leapfrog,” says Hemal Thakkar, director, CRISIL Market Intelligence and Analytics. He adds that the gap between Indian and international component makers in terms of technology, product offerings and competitiveness will shrink due to PLI. The auto component industry clocked $56.5 billion in revenues and $19 billion in exports in the last fiscal year.

While responding to ET’s query, EY India’s tax partners Saurabh Agarwal and Kunal Chaudhary say expansion of PLI to other sectors should be driven by global trade. “The Russia-Ukraine situation, for instance, has resulted in a global shortage of shipping containers and, therefore, container manufacturing potential in India may be exploited through PLI,” they say.

They also point to the government’s recent announcement of a national green hydrogen mission with a budgeted outlay of `19,744 crore to promote domestic manufacturing capability in the sector. Many in the renewables industry are hoping that the February 1 budget would roll out a new PLI for green hydrogen — a much-needed push for India to chase alternative energy sources.