The grain is vital to the diets of billions in Asia and Africa. Rice contributes as much as 60% of total calorie intake for people in parts of Southeast Asia and Africa, and that rises to 70% in countries like Bangladesh.

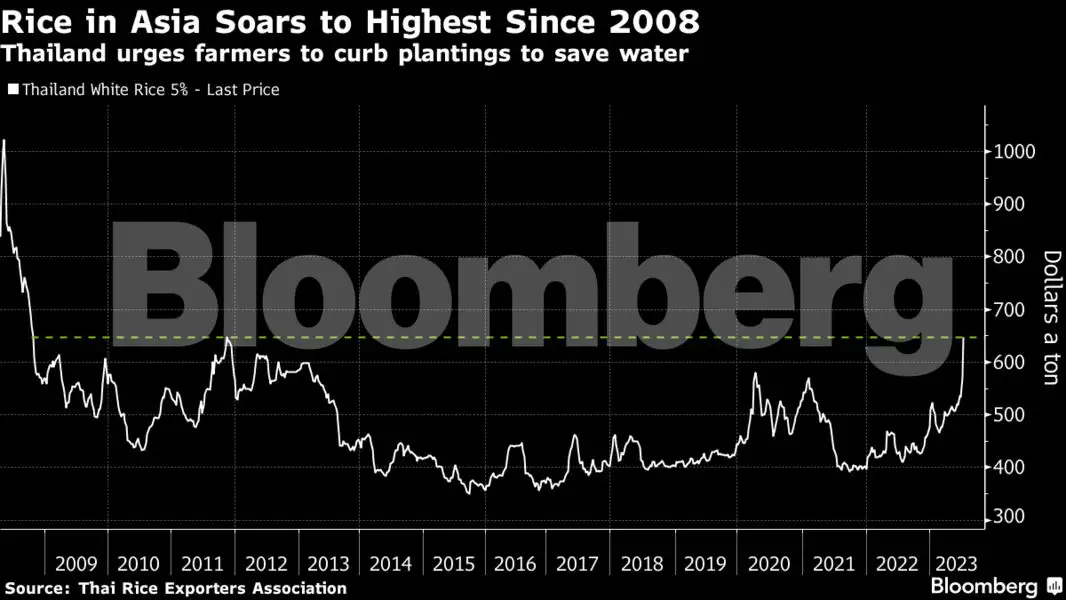

The latest price jump increases stress on global food markets already roiled by extreme weather and the escalating conflict in Ukraine. Thai white rice 5% broken, an Asian benchmark, climbed to $648 a ton this week as dry weather threatens Thailand’s crop, and after top shipper India — which accounts for 40% of the world’s trade — ramped up export curbs to protect its local market.

Bloomberg

Bloomberg“Higher rice prices will contribute to food inflation, particularly for poor households in the major rice consuming nations of Asia,” according to Joseph Glauber, a senior fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington. “Countries often follow suit when one country imposes export bans. The world’s poor are the biggest losers.”

Mounting concerns over tighter global supply are amplifying risks of a fresh wave of trade protectionism as governments look to ensure ample food reserves. The return of the El Niño weather pattern, which could dry up water-dependent rice crops in Asia, is exacerbating those fears.

“Rice is a more valuable commodity than before El Niño started up and Russia escalated its attacks on Ukraine’s wheat and corn exports,” said Peter Timmer, Professor Emeritus at Harvard University, who’s studied food security for decades. Prices could climb a further $100 a ton in six-to-12 months, he said.

“The big question is whether the price rise will be gradual, giving consumers time to adjust without panic, or whether there will be a rapid spike to $1,000 a ton or higher,” said Timmer, who worked with Asian governments on their policy response during the 2008 food crisis. That was when rice soared above those levels after export bans by major producers, notably India and Vietnam.

El Niño Risk

Most of the world’s rice is grown and consumed in Asia, where farmers are already grappling with heat waves and drought. Thailand, the world’s second-biggest shipper, is encouraging farmers to switch to crops that need less water, while farmers in Indonesia’s top rice-producing regions are planting corn and cabbages in anticipation of drought.

Bloomberg

BloombergThe biggest risk will be whether El Niño and climate change will disrupt agricultural production and drive overall food inflation higher, said Chua Hak Bin, a senior economist at Maybank Investment Banking Group in Singapore.

“This could trigger more protectionist policies, including export controls, which could exacerbate global food shortages and price pressures” he said. “Emerging market economies are more vulnerable to such food price shocks given the larger food weights in the consumer basket.”

Still, strict government-enforced price controls as well as food subsidies in many consuming countries could help keep a lid on inflation. The current episode looks “relatively tame” compared to then, Maybank’s Chua said.