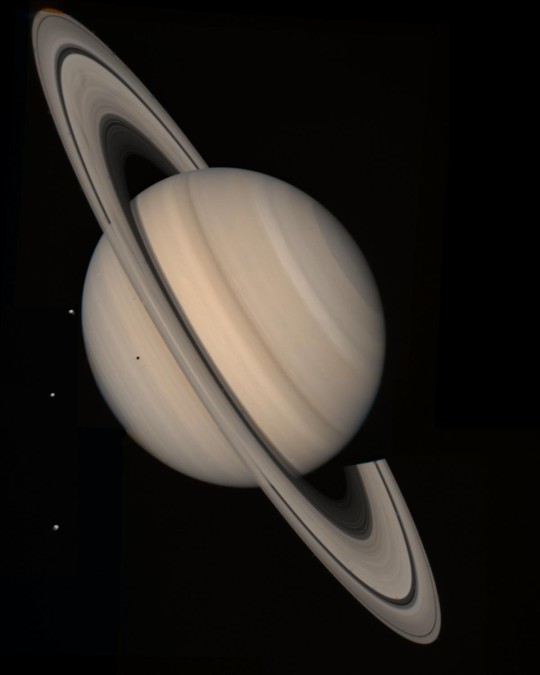

Saturn’s rings are eroding – at what could be a cosmic rate of knots.

Since the 1980s astronomers have known the Ringed Planet’s most striking feature is slowly disappearing, falling as icy rain into the atmosphere below.

However, they don’t know how quickly this is happening, or how long they have left.

Enter the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Since revealing its first stunning images in July last year, Nasa’s JWST has already contributed to numerous breakthroughs in the field of astronomy, not least potentially upending the entire timeline of the universe when finding the oldest galaxies ever seen.

Using the JWST and Hawai’i’s powerful Keck telescope, a team from Reading University plans to study the Saturn phenomenon in search of answers.

‘We’re still trying to figure out exactly how fast they are eroding,’ said team leader Dr James O’Donoghue. ‘Currently, research suggests the rings will only be part of Saturn for another few hundred million years.

‘We could be very lucky to be around at a time when the rings exist.’

A few hundred million years may not sound like they’re going anywhere fast, but on a cosmic timescale, they could be well into their twilight years.

‘I think it would be fascinating if the lifetime of the rings was only 100million years or so and that their age was billions of years,’ said O’Donoghue, speaking to Space.com. ‘That means we evolved just in time to see them before they vanished.’

Other estimates suggest the rings only appeared 100million years ago – meaning humans are lucky to have been alive to see them during their relatively brief existence in the solar system’s 4.5billion-year history.

The rings are thought to be made of billions of small chunks of ice and rock – pieces of comets, asteroids and moons that were broken up by Saturn’s powerful gravity.

They are aligned with the planet’s magnetic field lines, but that strong gravitational pull is drawing the inner rings towards it, which then fall as rain.

However, astronmer’s the Sun’s energy may also have an effect.

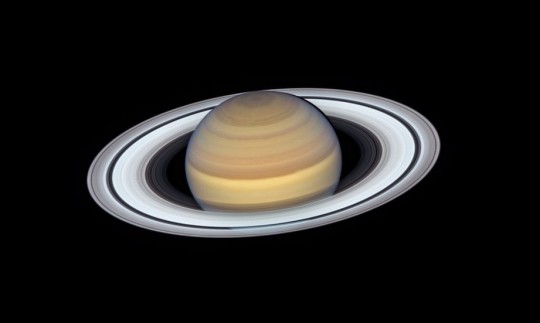

Saturn has a long year – it takes 29.5 Earth years to complete one orbit of the Sun, and each season lasts about seven years. Like Earth, Saturn is angled on its axis, meaning at different times of the year the rings will be ‘edge-on’ with the Sun, and at others tilted towards it.

‘We suspect that when the rings are edge-on with the sun, the ring rain will slow down,’ O’Donoghue told Space.com. ‘And that when they are tilted to face the sun, the ring rain influx will increase.’

To determine if this hypothesis is correct, the team will measure levels of a specific hydrogen molecule in the upper atmosphere which spikes when the icy ring rain is low, and dips when the rain increases.

‘Saturn may be many millions of miles away, but I believe the key to understanding how fast its rings are disappearing may lie with some of the world’s leading atmospheric scientists in Berkshire,’ said Dr O’Donoghue.

‘Working with the meteorology experts at Reading will give me the opportunity to finally find out what is going on with our giant planetary neighbour.’

MORE : Astronomers uncover mystery of most powerful phenomenon in the universe

MORE : Neptune’s elusive rings pictured by the James Webb Space Telescope