Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Oil & Gas industry myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

A dozen of the world’s biggest oil and gas companies are expanding a satellite monitoring campaign to detect methane emissions in emerging economies following detection of 26 large leaks of the planet-warming gas over Kazakhstan, Egypt and Algeria.

The Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, which includes Shell, Saudi Aramco and ExxonMobil among its members, told the Financial Times it plans to extend its year-long monitoring campaign, which ended in August 2023, to seven or eight new countries. It claimed the campaign is already reducing methane emissions.

As of October 2023, two operators in Kazakhstan and Algeria had plugged three big methane sources that, combined, were emitting 3,200kg of methane per hour, or the equivalent of the hourly carbon emissions from almost 4,000 petrol-fuelled cars.

OGCI is engaging with four operators to find solutions for the remaining emissions sources, according to a report due to be published on Monday at CERAWeek, a major energy conference in Houston.

The report does not reveal the identity of any of the operators responsible for the methane leaks, saying it is critical to build a relationship of trust rather than “name and shame”.

Bjørn Otto Sverdrup, chair of OGCI’s executive committee and a former executive at Equinor, a Norwegian energy company, said: “We are able to detect emissions and then use sophisticated technology to make the gas visible — that’s one step. Then we use the unique access that we have as companies to be able to engage with local operators even in remote geographies.”

The campaign by OGCI, which is a chief executive-led organisation representing roughly 30 per cent of global oil and gas production, comes amid growing focus by policymakers on the climate threat posed by methane emissions from oil and gas infrastructure.

The invisible gas is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere over a 20-year timescale. Experts estimate methane is responsible for almost a third of global emissions-induced increases in global temperatures since the start of the industrial era.

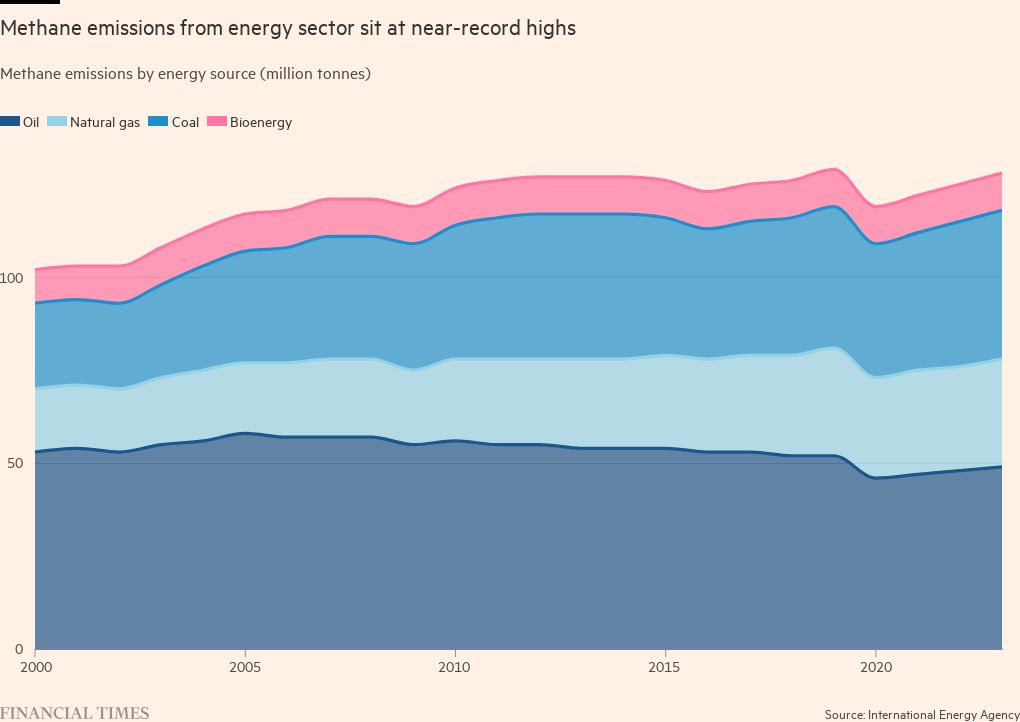

Despite pledges by more than 150 countries to crack down on methane emissions at COP28 in Dubai in December, emissions remain near record levels.

A report published by the International Energy Agency last week said the oil and gas sector was responsible for putting more than 120mn metric tonnes of methane into the atmosphere last year, a small increase on 2022.

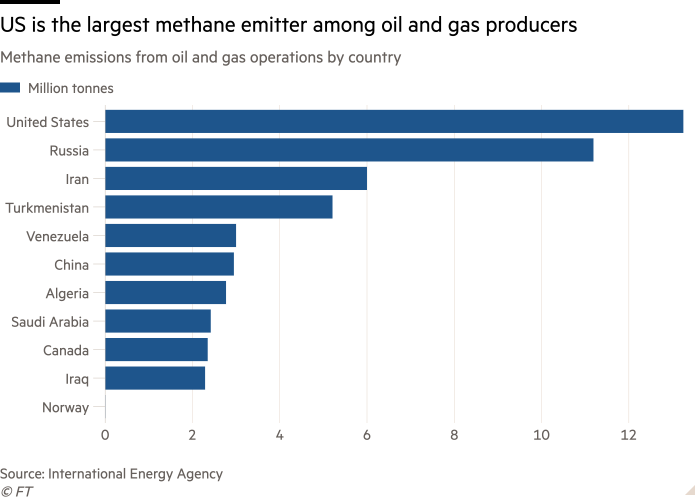

The US — the largest global producer of oil and gas — was also the largest emitter from oil and gas operations, closely followed by Russia, it said.

The OGCI report focuses on the group’s engagement with national oil companies and joint venture partners with extensive fossil fuel infrastructure and the use of satellite monitoring through its partnership with GHGSat, a company backed by a climate investment fund founded by OGCI. But it also highlights some of the challenges facing the industry in identifying and fixing methane leaks and reducing emissions in emerging economies.

Just 15 of the 26 large and persistent methane sources identified by satellite were subsequently confirmed on the ground by local operators. In some instances the leak may have stopped or it was not possible to find the source. Action to reduce emissions from the identified leaks still needed to be taken in many of the cases identified, according to the report.

The main sources of methane emissions identified were venting and incomplete flaring of methane from equipment and storage tanks, equipment and pipeline leaks, and incomplete combustion from burning pits of waste liquids and gases from fossil fuel production.

Satellite detection is an increasingly important tool in detecting methane leaks, particularly in emerging countries where there is often less focus on greenhouse gas emissions than in developed economies.

Andrew Baxter, an energy director at the Environmental Defense Fund, said the OGCI initiative is important because it combines satellite detection with peer-to-peer engagement and technical and financial support to tackle emissions.

“Maybe as long as methane emissions are being reduced, that’s enough. But I think transparency is a huge incentive for folks to act,” Baxter said, adding that a new methane-sniffing satellite launched by EDF this month would provide full transparency.

Additional reporting by Amanda Chu

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here