This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

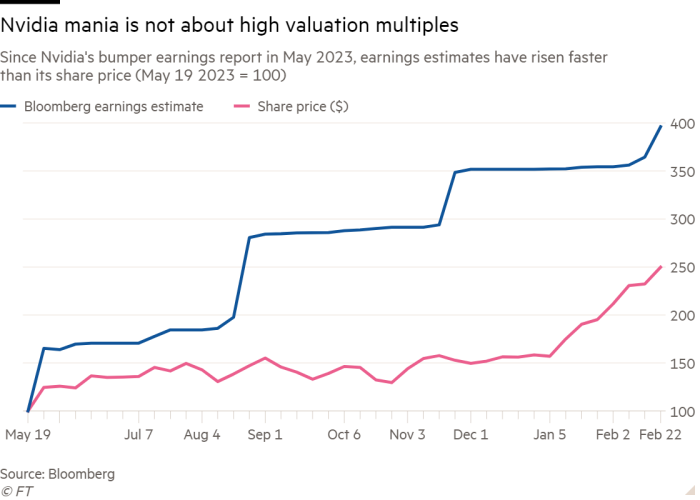

Good morning. Nvidia mania roars on. Shares were up 16 per cent yesterday after another improbably strong earnings report. Nvidia’s forward P/E ratio, at 33, is well above the market’s, at 21. Bubble talk is everywhere. But so is the counterpoint that in terms of valuation multiples, Nvidia doesn’t look all that insane. Since the company’s May 2023 blowout earnings, which launched the latest wave of AI hype, Nvidia analysts’ forward earnings expectations have risen faster than the share price:

Is the market crazy, or are analysts? Neither? Both? Email me: ethan.wu@ft.com.

Friday interview: Michael Mauboussin

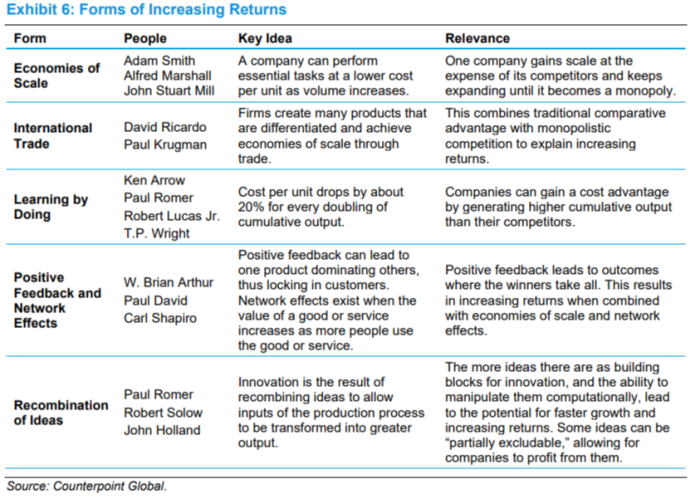

Two weeks ago, Unhedged covered a new paper about increasing returns to scale, whereby companies get more competitive as they get larger. It identified five sources of this phenomenon. Some are well known, such as economies of scale and network effects. Others are more obscure, but intuitive. “Learning by doing” captures the effect of extensive production experience on efficiency. “Recombination of ideas” gets at the fact that ideas multiply, a big deal for any company reliant on intellectual property. The five forces are summarised in this table:

Readers loved the piece. So we invited the paper’s author, Michael Mauboussin, Morgan Stanley Investment Management’s in-house wise man and an adjunct professor at Columbia Business School, for a longer conversation. In the interview below, Mauboussin discusses increasing returns, why they occur and how to invest in them.

Unhedged: You distinguish between five forces that contribute to increasing returns to scale. One way to sharpen your distinctions is to apply those categories to companies we all know. Uber, for instance, does not have great economies of scale — its unit costs don’t really go down as it gets bigger. But it has great network effects. Are there other companies that you think about in this context?

Michael Mauboussin: We’re making these categories appear more separated than they actually are. You could argue, for instance, that increasing returns from international trade is a function of economies of scale, or that it’s difficult to parse the difference between learning by doing and economies of scale. Of the five things we identified, a couple are more macro: ideas beget more ideas, international trade drives returns. And others are more micro, including economies of scale, learning by doing and network effects.

The notion that ideas beget more ideas goes back to Paul Romer’s endogenous growth theory. He makes a distinction between rival vs non-rival goods (whether one person’s consumption of a good prevents someone else from consuming it, eg, newspapers on a newspaper stand) and excludable vs non-excludable goods (whether it is possible to bar people from consuming a good).

This is a helpful lens. We cite an interesting book, The New Goliaths by Jim Bessen, where he makes the argument that large companies developing proprietary software represents a non-rival good that they’ve managed to make excludable. He argued that there’s been few attempts to diffuse those technologies. In contrast, automatic transmissions were developed by General Motors in 1940, and within a decade they were broadly diffused. For a century, the automobile industry has had essentially an open-source consortium for sharing ideas. Even though GM had patented their automatic transmission, other competitors could still put a version of it together.

Then there’s network effects. You mentioned Uber, which operates in a two-sided market and is a clear example of network effects. Economies of scale come into play, too. They’re a tech hub with employees writing software, which does scale.

Unhedged: But it doesn’t scale the way Microsoft does. Uber’s incremental cost, the cost of the next unit, is not zero as it is for Microsoft.

Mauboussin: They go down, though. Take a step back: what is powerful about network effects? Well, the value of the network is the value of the service increasing as more people use it. That increases willingness to pay, in economic terminology. The degree to which there’s a gap between price and willingness to pay is consumer surplus. At the same time, there’s classic supply-side economies of scale. Your cost per unit goes down as you write software and make your employees more productive as your network grows. So you get dual benefits.

Unhedged: Is it fair to sum your point up as: what changed between classical production economics and the new world of business is simply more non-rival goods with more clout in the marketplace?

Mauboussin: Yeah. One of the great academics on this is Carol Corrado. She notes that in the late 1970s, US companies’ tangible investments were in effect double their intangible investments. Today, that ratio has flipped: companies have about 1.5 intangible investments for every tangible investment. I’ve been working since the mid-1980s, so that’s in effect happened all in the span of my career!

Returning to network effects. In AT&T’s 1908 annual report, in talking about the telephone network, they describe network effects beautifully. The ideas of information economics are not new. They’re just more in the spotlight today. Paul Romer has written that you can think about businesses in two facets. One is the discovery of instructions, and the second is execution of instructions. Imagine a big steel facility at the turn of the 20th century — lots of brawn, lots of heat. There were clearly instructions, but it was mostly about implementation. By contrast, in a modern, high-flying biotech or pharmaceutical company, it’s mostly about instructions and very little about implementation.

Unhedged: Of course, the core instructions that Microsoft took advantage of were developed by Xerox. So another job is making sure that your instructions are put into use while remaining excludable.

Mauboussin: That was Romer’s main point. The idea of endogenous growth theory boils down to observing that innovation is mostly just recombining building blocks. In the original Apple, Steve Jobs unashamedly took a bunch of stuff from Xerox. The iPhone in your hand has five or six key technologies that were developed by the US government, largely by the Department of Defense. Those ideas or instructions were out there, and Jobs put them together brilliantly. But he could not have done it had those building blocks not been around.

Unhedged: So now I understand where increasing returns come from. How do I actualise that in a portfolio?

Mauboussin: It’s along the lines of what we’ve discussed, including Jim Bessen’s work on proprietary software that I mentioned. Our analysis shows, for instance, that returns on capital for large companies were generally lower than those for smaller companies in the 1980s and 1990s. The crossover point happened around 2000, and then the returns on capital for larger companies became quite a bit higher. That’s interesting.

You’ve seen a number of network battles: it wasn’t Uber by itself, it was Uber against Lyft in ride-sharing. Or when I think about electric vehicles or big cost reductions in batteries, how much of that is companies learning by doing? And if you have higher cumulative output than your competitors, what kind of advantage does that give you?

Unhedged: At the risk of oversimplifying, is it that in industries where learning by doing is important, you should bet that the leader by volume will be the leader in productivity and technology? Is the lesson just letting your winners run?

Mauboussin: Yes, though less in terms of technology and more in terms of productivity. We cited a study of US manufacturing facilities that ranked factories from one (the best) to 100 (the worst). The startling finding is that the rank 10 factory and rank 90 factory have a nearly 2x productivity difference. How can one manufacturing facility be twice as productive as another, when they’re both in the same country doing the same basic task? Part of it could be learning by doing, especially with respect to managerial talent and how best practices spill over.

If I want to catch the leader in electric vehicles, how do I do that if I’m constantly behind and their cumulative production is vastly greater than mine? That can be a tough gap to make up.

Unhedged: That point seems to rhyme with the fact that returns in stock markets follow a power law distribution. In other words, most of your gains over the long term come from a small number of stocks, even if you hold the market basket. Is it crazy to conclude from what you’re arguing that being heavily exposed to the Magnificent Seven is rational, since winners tend to be concentrated?

Mauboussin: We wrote a piece about this in the fall called “Birth, Death and Wealth Creation”, riffing off the Bessembinder data you referenced. Between 1926 and 2022, there’s been $55tn of wealth creation and 2 per cent of companies have created 90 per cent of that new wealth. It’s extremely skewed.

Underneath the hood, the top 20 companies are the obvious ones we’ve talked about, like Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon. But less obviously, the top 20 list also includes the likes of General Motors, General Electric, Exxon and Chevron. Partly, that’s a function of the methodology, which considers cumulative wealth creation in dollars. If you were a superstar in the 1950s or 1960s, you may have done well enough to keep on the leaderboard for a long time. So it reflects what happened in the past, and may not be a good predictor of ex-ante returns.

Do the underlying economics justify disproportionate market capitalisations for certain companies? That’s an open question. But our back-of-the-envelope numbers find that the economic profit of the Magnificent Seven is around 40 per cent greater than the aggregate economic profit for the Russell 3000. And we’re talking specifically about economic profit, measured as the spread between return on capital less cost of capital. So these companies are extraordinarily successful. You can argue about why, but the numbers are clear.

Unhedged: But in an industry exhibiting increasing returns dynamics, can you tell in advance which company will win out when it’s still a dogfight? Or is it just a casino for who gets to be the winner?

Mauboussin: It’s extremely difficult. Recall that even though Google had a better way of searching, in the late 1990s, they didn’t really have an economic model to complement their search abilities. They didn’t have a way to monetise. It took other things clicking into place for Google to establish themselves.

To give another example, in a two-sided market like ride-sharing, you can probably say a priori that it’ll be a winner-take-most market. But saying who will ultimately win out comes down to some combination of skill and luck.

The key question to ask: is it a company with a profitable economic model? VCR versus Betamax was a format war, and VHS won. But I don’t know that making VHS machines ended up being a good business. So it is one thing to become the standard, but the next question is whether you can monetise. Both have to be there.

Unhedged: I want to ask about a particular phenomenon. It seems like once you get huge in certain businesses, good things happen. So Amazon builds an enormous retail business that requires an incredible amount of computer power. But it’s used unevenly, so somebody says, why don’t we rent out the extra when we have it? And that idea builds a business, Amazon Web Services, that’s now more valuable than the retail business. That’s not necessarily a recombination of ideas. Where does that fit into your taxonomy?

Mauboussin: I co-authored a book with Al Rappaport in 2001 called Expectations Investing, and we dedicated a chapter to this topic called Real Options. A real option, like a financial option, is the right but not the obligation to do something. In a traditional valuation, you typically don’t explicitly consider the potential for real options. The real option literature started in extraction industries, but the story about AWS you described is a beautiful illustration.

When is having a real option important? You have to have a few things in place. First, you have to have an industry or business with a lot of uncertainty, because uncertainty and volatility drive option value. Second, you have to have a management team alert to cultivating and then exercising real options. Xerox came up with some killer technology, but never exercised their options to any degree of lasting success. Third, you have to have the resources to fund the option. AWS is a great business, but a very expensive business. You have to have capital to build the infrastructure. So you have to either be able to fund it internally or have economical access to capital markets.

Management teams can miss. The famous story about Intel starts with its Wintel standard [a collaboration with Microsoft] doing so well. Apple came to Intel first and said we’re trying to build a smartphone; we’d love you guys to build a chip. Intel ran the numbers and it didn’t look good, especially compared to the money they were making with the x86 chip running Windows. It’s some version of the innovator’s dilemma.

Unhedged: How do increasing-returns companies die, or see their returns collapse at last? Why don’t these things grow to the moon?

Mauboussin: In the 1990s, one of the great increasing-return stories was AOL. Classic network effects; all the boxes we would check. They decided to merge with Time Warner, which ended up not being great and allowing their competitors to fill the space. We allude to that in the economies of scale argument. You get the minimum efficient scale [the output level at which unit costs are minimised] and beyond that cost per unit starts rising because of diseconomies of scale, bureaucracy and so forth. You’re making so much money with your golden goose that you’re not innovating.

Another network effect business was the fax machine, which was simply superseded by better technology. Another example might be migration. Microsoft still has a strong share in their PC operating system business, but more and more we do our computing on our phones. And lastly, does your size or success raise the eyebrows of regulators?

Unhedged: The way we are discussing increasing returns in our public culture today is through a debate about antitrust policy. It’s Lina Khan and the neo-Brandeisians vs the ghost of Robert Bork and the Chicago school. Is the prevalence of increasing returns businesses in the modern economy a regrettable fact?

Mauboussin: We wrote a piece called “Market Share”, which discusses industry concentration in the context of mark-ups. Mark-ups are a key economic concept: price above marginal cost. Mark-ups were relatively modest from 1955 to about 1980; from 1980 they’ve been basically hockey-sticking up. When you zoom in, it turns out that it’s not industries distancing themselves from other industries. It’s actually firms within industries doing well — so-called superstar firms.

But the whole thing gets diluted if you introduce intangible investments in your calculation of mark-ups. Considering the sharp rise in intangible investments makes the increase in mark-ups look much more muted. I think people are getting excited about something that’s literally a calculation issue.

I don’t think anybody should argue that there’s an antitrust problem with a company doing well because of old-school economies of scale. I mentioned those differences in factories earlier. You’re not going to walk up to factory number 10 and say, hey, stop doing this! Factory 90 is falling behind! They’re just better at what they do. So the only question is: are companies being anti-competitive? With software, that’s difficult. Network effects exist. That can create consumer surpluses, as we discussed earlier. It seems to me like most consumers don’t have a big problem with Google and Amazon. They basically like these companies.

While writing about industry concentration, I realised how much of a mess it is. So much depends on your methodology. I can bring in two credible economists who can give you different answers with the same data set. The FTC has had a chilling effect on mergers. But it hasn’t had a great record in court, perhaps because demonstrating consumer harm is so hard. It’s a very complex topic, and very difficult to establish something that seems simple.

One good read

Russia’s poisoning operation.

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.