When Lauren Stanley, an insurance broker from Kent, bought her two-bedroom new-build flat in Tonbridge for £180,000 in 2013, she had no idea that it came with a problematic ground rent arrangement. It wasn’t until she attempted to sell the property, and saw three buyers pull out, that she learned what was putting them off.

“Once my third buyer pulled out, I was advised that I have a rising ground rent clause, which sees the fee increase every five years in line with inflation,” she says. The first increase took it from £250 to £320, and if it carried on increasing by the same percentage, by the end of the 115-year lease term it would have been an extortionate amount. She put the eventual figure at more than £100,000 a year.

What’s more, her ground rent is now higher than the £250 threshold above which a lease turns into an assured shorthold tenancy agreement. Under this kind of contract, a leaseholder can be evicted if they fail to pay their ground rent for three months.

Stanley says she had to extend her lease to remove the ground rent, and after a nine-month battle with “very reluctant freeholders”, reached an agreement that cost her £20,000 – a £13,000 charge plus her own and the freeholders’ solicitors’ costs, which she says was “my entire savings”.

The freeholder is Adriatic Land 3 (GR1), which is owned by UK pension funds and managed by Long Harbour, an investment fund whose chief executive and part owner is William Waldorf Astor, eldest son of the fourth Viscount Astor. His half-sister is former prime minister David Cameron’s wife, Samantha.

The fund says it is the second-largest manager of freeholds in the UK, with a £1.4bn portfolio of 190,000 leasehold properties.

London company HomeGround, which administers properties on behalf of Long Harbour, says it made two offers to change Stanley’s lease: first to one where ground rent goes up in line with inflation every 10 years, which it claims is accepted by the majority of banks; and then to a 25-year inflation-linked increase. “We were therefore surprised that the leaseholder chose to go through the lease extension process, given the costs and time that entails,” said a spokesperson. Stanley says her solicitor advised against accepting either offer, and she felt she could not take the risk of losing another buyer.

Michael Gove, the housing secretary, has pledged to tackle ground rents as part of the leasehold reform bill now making its way through parliament. He has described the system as “feudal”. The new legislation will ban leaseholds on new houses in England and Wales, but not on new flats. It will also make it cheaper and easier for leaseholders to extend a lease, buy the freehold and take over management of their building.

For centuries there has been a two-tier system of property ownership in England and Wales. Leaseholders do not purchase their homes outright but are a tenant of the freeholder, who owns the land on which the property stands. They pay ground rent to the freeholder for the land. The average lease runs between 99 and 150 years. Properties with short leases are difficult to sell, and extending a lease with less than 99 years to run can cost tens of thousands of pounds.

Among the UK’s biggest land owners are King Charles and, separately, the crown estate, which belongs to the reigning monarch; the Duke of Westminster via his property group Grosvenor; and the Duke of Bedford, whose estate includes Woburn Abbey.

Much of the land they own is agricultural, but they also make significant incomes from leasehold properties. Much of central London is still owned by Grosvenor, as well as by the Church of England, the crown estate, the Portman estate –which dates back to the 16th century and is still held in trust for Viscount Portman and his wider family – and the Howard de Walden and Cadogan estates, both still in family hands.

In written evidence to a parliamentary committee, Grosvenor said it would oppose any move to do away with leaseholds entirely. “We cannot support abolishing leasehold for flats, as there is no workable alternative at present. Parliament should proceed cautiously given the impact this could have on the new flats market, and existing leaseholders.”

Quick Guide

A history of leaseholds

Show

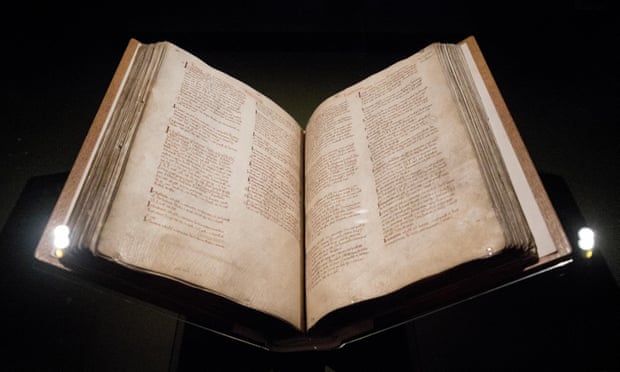

The term “freehold” – meaning the full, outright ownership of land – dates back to the Domesday Book of 1086 (pictured), the survey of much of England and parts of Wales made at the behest of William the Conqueror.

The first “leasehold” appeared a few decades later – a concept to allow “villeins” or “serfs” to work a plot of land for a fixed period in return for payment in kind – food or services – to the landowners.

Freeholders held a dominant position until the 1920s, when legislation was introduced to limit rents and restrict the right of landlords to evict tenants. Landlords began selling long leases, ranging between 99 and 125 years, on their properties to generate more revenue without losing ownership of the land.

This was the beginning of the leasehold system that we know today, according to Sarah Dwight, who sits on the Law Society’s conveyancing and land law committee. As city living changed, with more apartments and fewer single-occupier houses, leasehold ownership rose as the number of flats constructed shot up.

Unlike London, Scottish city centres have not been owned for centuries by a handful of families or their trusts – and Scotland’s minimal form of leasehold ended in 2012.

Like many other countries, including Australia and the US, Scotland has what is known as a “commonhold” or condominium system. However, critics say that flat owners in large apartment blocks may struggle to co-manage them under such ownership. Commonhold was introduced as a type of property ownership in England and Wales in 2004 as well, but only a few have been created since then.

Guy Shrubsole, author of Who Owns England?, says the country continues to have a “quasi-feudal system” of land ownership.

Shrubsole estimates that “the aristocracy and gentry still own around 30% of England” – and that figure may be higher, as 17% of freehold land in England and Wales is unregistered. The owners are likely to be aristocrats, whose estates have been in their families for centuries.

A further 17% of England is owned by “a handful of newly moneyed industrialists, oligarchs and City bankers,” says Shrubsole. The vast majority of the population owns very little land or none at all. Land under the ownership of the royal family amounts to 1.4% of England.

When Natalie Walton bought her new-build two-bedroom flat in Wakefield for £105,000 four years ago, she had no idea that on top of her £1,600 annual service charge, her ground rent could be increased every 20 years.

“It’s not easy when you’re a first-time buyer to understand all of the implications of ground rents. I had a copy of the lease but the solicitor didn’t go through any of it with me,” says Walton, 45, who works in art and community engagement. Her ground rent went up from £150 to £301.60 last year, in line with inflation over the preceding 20-year period.

“You’re renting land and you get nothing in return in terms of any support. I used to rent this flat, and if there was a maintenance problem, the landlord paid for it. So what’s the argument in terms of paying a [ground] rent and then getting absolutely nothing in return?”

Walton’s freeholder is Fairhold Holdings, a company owned by the family trust of financier Vincent Tchenguiz until it was acquired by pension funds. It, too, is managed by Long Harbour.

Responding to Walton’s comments, the company’s HomeGround arm said: “Ground rent is different to service charge and is a payment in consideration of ownership rights. However, it does allow for the presence of professional freeholders … to take on the long-term stewardship obligations for apartment buildings, providing professional support to residents in respect of their buildings. This support ranges from overseeing health and safety issues, remediating building safety or life safety defects, providing instructions to managing agents, managing complex issues between leaseholders and ensuring leaseholders have peaceful and quiet enjoyment of their property.”

Walton’s service charge covers building insurance and a sink fund for emergencies, but does not cover all maintenance, and she recently paid £1,100 towards roof repairs. The estate of 200 flats and 50 houses is managed by an agency appointed by the leaseholders. “The freehold pays for nothing. It’s literally giving someone money for nothing,” Walton says.

Housing campaigner Harry Scoffin calls freeholds “a completely unnecessary rent extraction industry”.

A fifth of all properties in England are leasehold homes. Far from being phased out, their numbers are increasing: from 4.65m in 2019-20 to 4.98m in 2021-22, according to the government. About 70% of them (3.5m) are flats, the rest (1.5m) houses. London and the north-west have the highest proportion of leasehold dwellings, at 36% and 32% respectively, much higher than all other regions in England which had between 9% and 17%.

It was in the 1990s that property investors realised they could make money from buying freehold titles and pushing up ground rents. In the postwar years, new-build estates were typically sold as freehold, but then big developers such as Persimmon, Taylor Wimpey, Barratt and Bellway changed course. Many of their new homes were sold as leaseholds, with the underlying freehold initially held by the developer, then sold to property investment firms. The number of new-build leasehold homes doubled from 22% in 1996 to 43% in 2015.

Gove’s recent proposal to reduce ground rents to a nominal value, effectively zero, sparked fierce opposition from the Residential Freehold Association and the British Property Federation (BPF), which says doing so without compensating freeholders would be open to legal challenge.

Leaseholders would save a combined £5.1bn in ground rent over 10 years, the government estimates. With 4.5 million leaseholders in England and Wales who report paying ground rent (they make up 86% of all leaseholders), the average saving would be £1,136 per home. As well as lost ground rent, freeholders face a £27bn loss in asset values, resulting in a total hit of £32.4bn, the government estimates. It says it has no plans to pay compensation for lost revenue.

The bill was introduced after a scandal over spiralling ground rents on new-build homes, exposed by the Guardian and other media outlets, which revealed that some were doubling every 10 years. The Competition and Markets Authority launched an investigation into unfair practices in 2019. It helped about 20,000 leaseholders seek redress from developers and freeholders, and the government abolished ground rent for new leases in the summer of 2022. However, it says a “significant” number of leaseholders will still see ground rents rise sharply in coming years.

Freeholders argue that savers will suffer because pension funds have invested in ground rents, attracted by the predictable long-term income stream. They also claim the changes could lead to higher home prices and poor property management.

Ian Fletcher, the BPF’s policy director, says: “There’s a danger of replacing one scandal with another if the government raids pension funds to the tune of £32.4bn.” Pension funds would resort to legal action because of the impact on savers, he says. “For the sake of those beneficiaries, some would be compelled to take legal action.”

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities counters that less than 1% of pension funds’ assets are invested in residential properties. But Joe Dabrowski, deputy director of policy at the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association, says repercussions could include a shortfall in pension scheme assets: “Additionally, there’s the risk of damaging the reputation of the UK investment market due to retrospective changes to investment terms made in good faith.”

The financial fallout has begun. Time Investments suspended its £200m Time:Freehold fund after its independent valuer expressed “material uncertainty regarding the fund’s residential property valuations”. The Ground Rents Income Fund, advised by Schroders Capital, the only such listed fund, will wind down over the next couple of years.

Jack Spearman, RFA head of leasehold, says: “Others would just call it theft, but effectively you’re transferring value … from pensioners to leaseholders. The majority [of freeholders] will go insolvent … [and] that has issues for insurance, maintenance and repair of all these buildings.”

Supporters say the reforms should boost property sales. Many mortgage lenders don’t lend on properties where the ground rent exceeds 0.1% of property value. Sebastian O’Kelly of the campaign group Leasehold Knowledge Partnership says: “Loads and loads of flats in the country have ground rents that are more than 0.1%. So if the government loses its nerve and keeps ground rents as they are, thousands of people are not going to be able to sell their properties.”

A final decision from government is expected in March. For many, the reform bill won’t go far enough. There are calls from legal experts and leaseholders for a “commonhold” system, as used in other countries, that abolishes all leaseholds.

Christopher Hodges, emeritus professor of justice systems at Oxford University, says: “The introduction of commonhold is a modernisation that would simplify so much about how people own, manage, and live in homes. It is long overdue.”

Labour has said it will introduce it for all new properties if it wins the general election, and shadow housing minister Matthew Pennycook tweeted in November: “We also need to completely overhaul the system so that existing leaseholders can enfranchise much more easily and move to commonhold if they wish.”

O’Kelly at the Leasehold Knowledge Partnership says the reforms should go further. He wants the entire system abolished: “You’re out of step with the rest of the world, so stop creating more leaseholds.”

Big names in the property game

Vincent Tchenguiz and family The family trust of the financier Vincent Tchenguiz owns Consensus Business Group, which has acquired or manages more than 250,000 residential freeholds. It describes itself as the largest owner and asset manager of residential freehold interests in the UK. A large chunk of the ground rent income from its £4bn portfolio now goes to the pension investor Rothesay Life, which was set up by Goldman Sachs and is now owned by the Singaporean sovereign wealth fund, GIC, and the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company.

Long Harbour A real estate investment firm run and part-owned by William Waldorf Astor, half-brother-in-law to David Cameron, Long Harbour says it is the second largest manager of freeholds, with a £1.4bn portfolio of 190,000 leasehold properties. It manages them on behalf of academic endowments, charities, family offices, pension funds and other investors. Astor worked for Consensus for six years before leaving in 2009.

Count Luca Rinaldo Contardo Padulli di Vighignolo The Italian aristocrat owns the parent company of Wallace Partnership Group, which says it owns and manages 103,000 freehold titles in England and Wales.