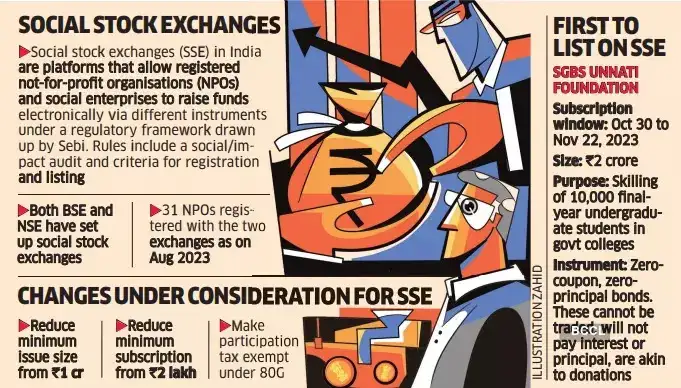

Unnati, which works on skilling underprivileged youth to increase their employability, is set to be the first NGO to list on India’s new social stock exchanges (SSE) later this month, following its zero-coupon, zero-principal (ZCZP) bond issue that opened on October 30. But with everything around it being so new, challenges were aplenty. “When I approached the Registrar of Companies and said I needed to file a particular form, they asked me what a social stock exchange was,” he laughs. The last date for the Rs 2 crore issue was originally November 7 but has been extended to November 22. Director AS Narayanan says this was to ensure the issue will be fully subscribed. “We are sure it will be—it’s just a matter of time,” he says. Swamy, too, is optimistic. “The (stock) exchanges have been extremely proactive. It’s a work in progress but it was important that this happens now since the SSE was announced in 2019.”

Four years ago, in the July 2019 Budget, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman proposed setting up an electronic fund-raising platform “under the regulatory ambit of Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi)” for listing social enterprises and voluntary organisations that are “working for the realisation of a social welfare objective so that they can raise capital….” Following multiple consultations, SSE platforms were set up as segments on the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and the National Stock Exchange (NSE) in 2022 and early 2023, respectively.

With the first listing under way, there is finally a sense of optimism. R Balasubramaniam, who heads the Sebi advisory committee on SSE, is hoping for another 5 listings next month and 20 by the end of the financial year. Hemant Gupta, who heads the BSE SSE, is more cautious and says there are several in the pipeline, with at least two-three more this year, which will set the momentum. “A lot of new ground had to be covered such as coming up with a new instrument like ZCZP, which is neither an equity nor a bond but also meets Sebi’s comfort levels. Overall, I’m satisfied with the progress,” he says. All stakeholders agree that even though the process has begun, wrinkles are still being ironed out and change will not happen overnight.

HELLO, RETAIL DONORS

A social stock exchange is a platform for for-profit social enterprises and/or not-for-profit organisations, which aim for social impact, to raise capital. Countries like Canada and the UK have experimented with various models of SSE. “If you look at the journey of SSE, several emerged over the last few years, but most have gone,” says Balasubramaniam, who feels India can learn from others’ mistakes. While it took time to get the initiative off the ground in India, Balasubramaniam, founder of the nonprofit Grassroots Research and Advocacy Movement, says he is confident of its success for multiple reasons, including government support, a more mature ecosystem and factors like a fund to build capacity for the new process.

A nonprofit wishing to list on a social bourse needs to first register with it and meet a host of criteria, make annual disclosures and produce extensive documentation, just as a company planning an IPO would. This includes a detailed fund-raise document with financial statements, risks, past social impact and the strategy to achieve its vision. To mobilise funds on an SSE, NGOs can currently issue zero-coupon, zero-principal bonds, instruments which will not give you interest or return the principal and are essentially like a donation. Other instruments like mutual funds have also been recommended. Both NGOs and for-profit social enterprises will have to go through annual social audits to gauge impact. Gupta says while the exchanges are meant for both NGOs and social enterprises, the bulk of interest is from the former. “The regulations began to be issued from July 2022. Since then, scores of NGOs have come forward and shown interest but very few social enterprises.” At the end of August, 31 nonprofits had registered with both exchanges.

Currently, nonprofits raise money largely from philanthropic foundations, high net-worth individuals, corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds of companies and foreign donations, though the current Union government has considerably tightened the rules around the last. One aim of launching a social stock exchange is to increase fund-raising avenues by including more individual, or “retail”, donors. “Retail giving continues to be vastly untapped in India and is largely informal, such as donations to religious institutions or to the needy one knows. I feel this will bring in a larger pool of donors to the sector,” says Pushpa Aman Singh, founder of the NGO repository GuideStar India and member of Sebi’s advisory committee for SSE. The India Philanthropy Report 2023 by Bain & Company and Dasra estimates that only 22% of the contribution value of retail giving in India is from formal giving.The hope is that the extensive documentation and criteria that listing entails will attract more donors by increasing transparency and accountability. “We work with lakhs of donors on the GiveIndia platform. One of the biggest concerns we hear all the time is around trust: how can we trust that the money we are giving will be fully utilised and create the impact it claims?” says Atul Satija, CEO, GiveIndia, an online donation platform. “This is a huge problem and needs a lot of attention so I, personally, feel social stock exchanges are a welcome move.”

By having a broader donor base, the idea is that the influence of an individual with disproportionate capital on the development paradigm will be limited, says Vineet Rai, founder, Aavishkaar group, and member of the first working group on social stock exchanges. “Concentrated funding by a philanthropist or foreign donor can make a nonprofit organisation prone to their influence and could go against the national interest—that was the thought process.”

To appeal to a wider base and simplify the process, various changes are under consideration, such as giving tax exemption to the purchase of bonds, reducing the minimum application size from `2 lakh to `10,000, reducing the minimum issue size from `1 crore and allowing CSR funds to participate. To reduce the cost of application for NGOs, money from the capacity utilisation fund could be used. Says Unnati’s Swamy: “I was fortunate that the law firm Trilegal and the financial advisory firm Unitus Capital offered their services pro bono for the issue. Otherwise, that would have cost me at least `10 lakh.” For Unnati, the bond issue is not just about raising funds, he says. “This gives NGOs a chance to say our governance and social impact are perfect, which is very powerful. I have been in this space since 2011, but donors still grill us about our credibility.”

Being the first off the block, all eyes are on how the issue will perform. Unnati needs to raise at least 75% of Rs 2 crore to avoid being under-subscribed. But even if this issue is a success, social stock exchanges will take time to become mainstream. GuideStar India’s Singh says one should not worry if the inflection point takes 15-20 years as it is critical to get the architecture right.

Aavishkaar’s Rai says it will take less time and predicts that adoption will follow a “J curve”, wherein a novel idea takes a reasonable amount of time to get accepted, but once it does, finds scale. “I don’t expect the SSE to set everyone’s imagination on fire for another two years. But in five, it will be one of the most acceptable ways for both domestic and foreign capital to engage with India’s developmental thought process.”