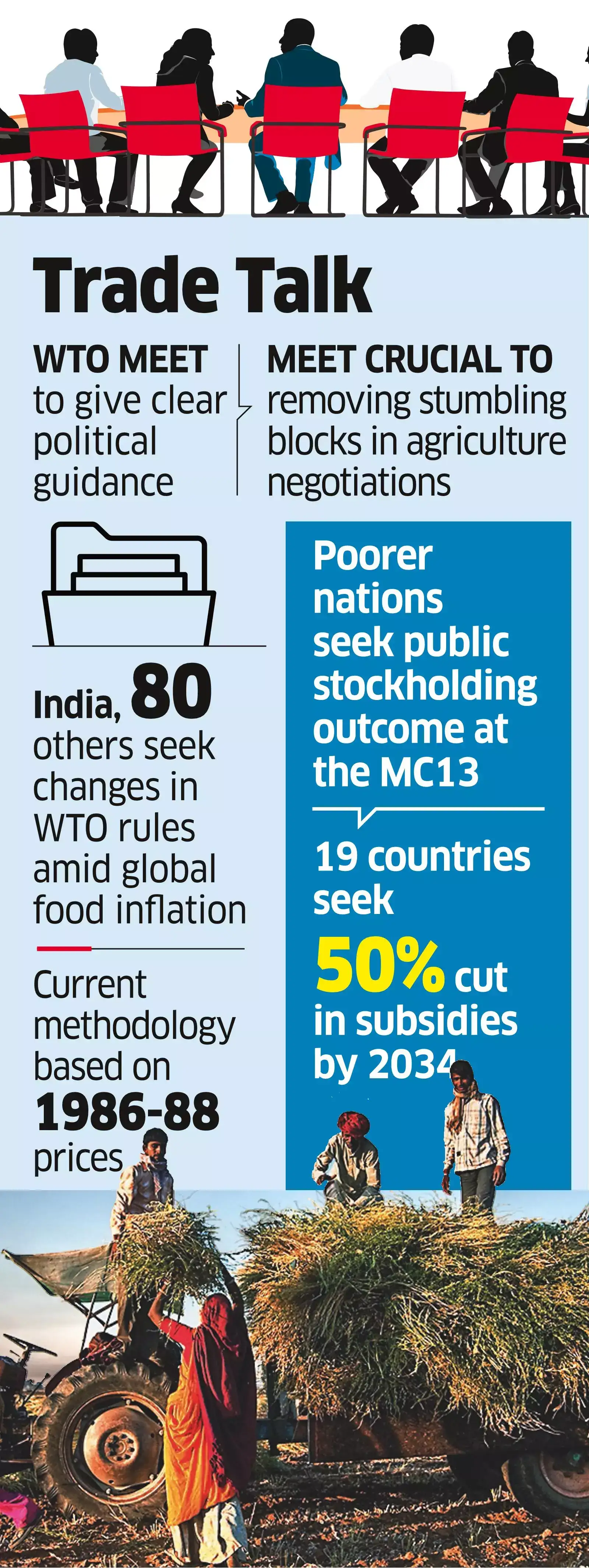

The meeting, to be held Tuesday, follows India’s criticism of the Cairns Group for proposing to halve the overall agriculture domestic support entitlements by the end of 2034 and “ambushing” public stockholding talks.

Around 80 WTO members opposed this proposal by the Cairns Group, which has 19 members including Argentina, Australia, Brazil and Canada. Last month, the European Union had shown willingness to negotiate the public stockholding issue with India. The move was seen as a significant breakthrough on the issue which has been deadlocked for the past 10 years.

ET Bureau

ET Bureau“The meeting aims to provide clear political guidance to overcome the stumbling blocks in the agriculture negotiations,” said an official, who did not wish to be identified.

The mini-ministerial meeting assumes significance as India and 80-odd developing and least developed countries want an outcome on public stockholding to be at the core of any potential agriculture package at the 13th ministerial conference (MC13) of the WTO next year.

Last month’s meeting of senior officials could not give a clear sense of direction on the talks.The G33, African Group and the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States are seeking the fulfilment of the existing mandate and the adoption of a permanent solution at MC13 after the deadline was missed at MC11 in Buenos Aires. They have proposed to amend the anti-circumvention clause in the Bali Ministerial Declaration of 2013, as per which developing countries who procure food stocks for security “do not distort trade or adversely affect the food security of other members”. They have said that a permanent solution for public stockholding should account for inflation and also be based on a recent reference price instead of an old one, which is based on 1986-88 prices.

Public stockholding is a policy tool used by governments to purchase, stockpile and distribute food when needed. Developing countries’ food subsidies are protected by an interim peace clause, which shields food procurement programmes against action from WTO members in case the subsidy ceilings – 10% of value of food production in the case of India and other developing countries – are breached.