The bad news is what’s been causing that cooling: emissions of fine particles of sulfur and nitrogen compounds and carbon, known as aerosols. Like spray aerosols, these are fine particles suspended in the air — but hardly any come from aerosol cans. Most are produced by the same processes of burning carbon-rich fuel that cause greenhouse-gas emissions. The particles float in the atmosphere, affect the formation of clouds, and reflect solar radiation back into space. That counterbalances the warming effect of carbon dioxide, methane and other gases. As a result, increased aerosol emissions cool the atmosphere, while reductions warm it.

Reducing aerosol emissions should be a key priority for global health, however. There were about 4.23 million excess deaths in 2015 caused by exposure to such chemicals. The worst effects were caused by inhaling smoke from wood and dung fires in poor countries, and transport fuels and road dust in rich ones.

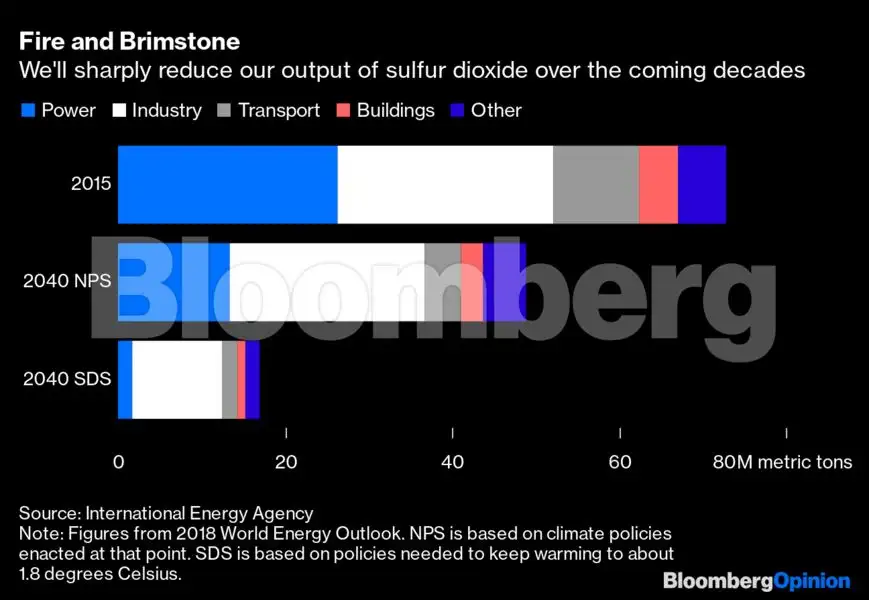

We’re making progress on that front. Concentrations of sulfur dioxide or SO2 in Europe and the US have been declining since the 1980s, when fears about acid rain caused power stations to install scrubbers to remove sulfur compounds from smokestacks. Similar regulations have been drastically reducing power plant aerosol emissions in China and even India, where a government push to roll out LPG stoves has also been cutting smoke from domestic cooking.

Bloomberg

BloombergThat progress on the health front, however, means the cooling effect that aerosols have provided since the dawn of the industrial era is disappearing — a setback in climate terms. As a result, even a fall in carbon emissions may be insufficient to halt the heating of the planet.

“It could be as important as warming from CO2 over the next few decades,” says Natalie Mahowald, a professor at Cornell University. “Temperatures will increase as aerosols are cleared up for air quality.”

The effects of this have already been measured in some areas. The Covid-19 lockdowns in early 2020 may have caused temperatures to increase as much as 0.3 degrees Celsius in parts of the northern hemisphere, with warming from attenuated aerosol emissions overwhelming cooling from the reduction in greenhouse gases.

Solar radiation at ground level in Wuhan almost doubled at the peak of China’s lockdowns thanks to reductions in aerosols, a group of Chinese researchers found this month. Falling levels of nitrogen oxide may have changed the balance of chemical reactions in the atmosphere and lifted concentrations of methane, a particularly potent greenhouse gas, according to a 2022 separate study.

Regulations introduced in the same year, which banned high-sulfur fuel oil from shipping fuel, may have further reduced sulfur dioxide, the most important aerosol for cooling the atmosphere. One recent study found that sulfur control rules introduced in China between 2016 and 2019 cut regional SO2 emissions by as much as 40%.

Geoengineering (the idea of arresting global warming by spraying SO2 into the atmosphere and dimming the sun) is normally treated as the stuff of science fiction, or at least madcap proposals by out-of-control startups. What these studies show is that, to the contrary, we’re already doing geoengineering, except in reverse — heating the planet instead of cooling it.

Bloomberg

BloombergThat will make the coming decades particularly challenging. Aerosols typically disappear from the atmosphere within a matter of weeks, whereas CO2 hangs around for as much as 1,000 years. As a result, when you clean up your smokestack emissions, the bad outcomes last longer than the good ones.

We’re at the “turning point of the aerosol era,” researchers at NASA’s Goddard Institute concluded last year, with their cooling effect already as weak as it’s been in a century. As a result of that shift, warming could be as much as twice as rapid between 2010 and 2050 as in the previous four decades, according to a recent study led by Columbia University climate scientist James Hansen.

The good news, according to Bill Collins, a professor of climate processes at the UK’s University of Reading, is that we’re already incorporating these changes into our models of future climate change. Reducing aerosols should remain a priority, says Mahowald, because for the next few decades they will still be killing more people than climate change, with particularly damaging impacts on poorer and non-White groups who are more exposed to such emissions.

There are a few win-win options, too. Soot from burning fields and forests, from wood and dung fires, and from diesel fuel is a rare aerosol that warms the atmosphere instead of cooling it. Cutting output of that pollutant will help both sides of the climate change equation. Nitrogen oxides from aircraft can warm the atmosphere even as ground-level emissions cool it, says Collins, so cleaning that up should also be a priority.

We nonetheless face a hazardous path out of the situation we’ve brought to the world. For all the prominence of carbon dioxide in the discussion of climate change, it’s just one of the ways in which human activity has upset the atmospheric equilibrium which we’ve enjoyed since the dawn of civilisation. It will be far harder to restore that balance than it was to disrupt it.