Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A stronger than forecast US inflation figure caused a stir as European Central Bank rate-setters sat down for dinner on Wednesday — but several attendees said it only toughened their resolve to disregard what the Federal Reserve might do.

The ECB, which on Thursday decided to keep its benchmark deposit rate at an all-time high of 4 per cent while signalling a cut was likely in June, is grappling with intensifying questions about how much it would cut borrowing costs if the Fed took a different path.

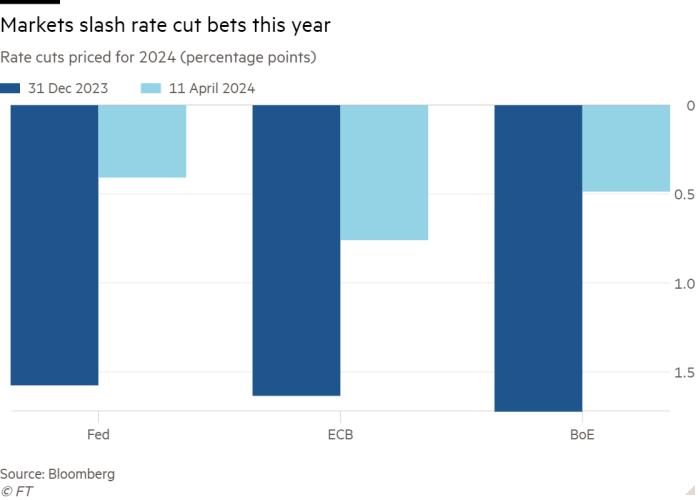

US data on Wednesday showed a 3.5 per cent rise in consumer prices for the year to March, compared with expectations of 3.4 per cent. The third successive month of above-forecast inflation prompted traders to bet US rate cuts might undershoot expectations and not begin until November.

“We are not Switzerland, we are the euro area and can operate independently without worrying about the exchange rate,” one ECB governing council member told the Financial Times. Another said: “It would actually be illegal for the ECB to decide policy based on what the Fed was doing.”

There was some dissent over the ECB’s decision to keep rates on hold on Thursday. But several of those present said no more than three out of 26 council members forcefully argued for cutting rates immediately. However, one who pushed for a cut said six others had done the same.

The ECB has clearly signalled that with the eurozone economy predicted to grow only tepidly this year and inflation falling towards its 2 per cent target — after dropping to 2.4 per cent in March — it expects to start cutting rates in June.

All officials contacted by the FT brushed off concerns about transatlantic divergence on monetary policy and expressed confidence they would easily agree to start cutting its benchmark deposit rate from its record high at their next meeting on June 6.

“We would need some kind of geopolitical shock or two very bad inflation readings not to cut rates in June,” said one council member. A second said: “All colleagues agree we should diverge from the Fed — everything here is pointing to a reduction of inflation.”

A third said: “We discussed this quite a bit over dinner when the US inflation numbers came out on Wednesday and basically we’ve got to focus on our mandate and not get distracted by what the Fed might do.”

The ECB declined to comment on the council discussions. Its president Christine Lagarde dismissed reporters’ questions on Thursday about whether its decisions would be swayed by the Fed. “We are data-dependent, not Fed-dependent,” she said, pointing out that inflation in the US was “not the same” as in Europe.

Council members agreed with Lagarde’s assessment, pointing out US inflation was being kept higher by relatively strong economic growth and the expansionary fiscal policy of President Joe Biden’s administration. “We are confident of hitting our inflation target and the US data didn’t shatter that confidence,” said one.

But traders in swaps markets on Thursday slightly downgraded the likelihood that the ECB will begin cutting rates in June to around 70 per cent, from 75 per cent earlier in the day.

Some economists reckon the ECB will try to avoid cutting rates much more aggressively than the Fed, partly out of fear of weakening the euro and so further stoking inflation. There are also concerns eurozone inflation could soon mirror the recent resurgence seen in the US.

“We disagree with what Christine Lagarde said regarding US inflation and the full decoupling of eurozone inflation developments from those in the US,” said Carsten Brzeski, global head of macro at ING, pointing out that US price growth had “nicely led eurozone developments with a lag of around half a year”.

He added that the eurozone was likely to experience similar “structural constraints to the supply side” as the US, such as “the lack of skilled workers, capacity constraints due to under-investment, or energy and commodity dependencies”.

Greg Fuzesi, an economist at JPMorgan, said that “US inflation developments also have some relevance” for the ECB. He cited the recent stickiness of eurozone services prices — which have risen at an annual rate of 4 per cent for five months — as an example of how “incoming data are providing some challenge to the ECB”.