This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Tuesday

The Federal Reserve revealed it was not itching to cut rates as early as March after its meeting last Wednesday, a view that will have been reinforced by very strong US jobs figures on Friday. As things stand, the meeting on March 20 will be more important in setting out how many rate cuts the Fed thinks are necessary in 2024 rather than immediate action. Are financial markets right to scale back their expectations of US rate cuts in 2024? Email me: chris.giles@ft.com

Swati Dhingra on her vote to cut UK rates

Though most eyes were on the US Federal Open Market Committee last week, the Bank of England’s pivot towards rate cutting was in many ways more interesting. The UK central bank’s forecasts were logical and the communication of its dovish switch was smooth and effective. It has been a very long time since I have been able to say that about the BoE.

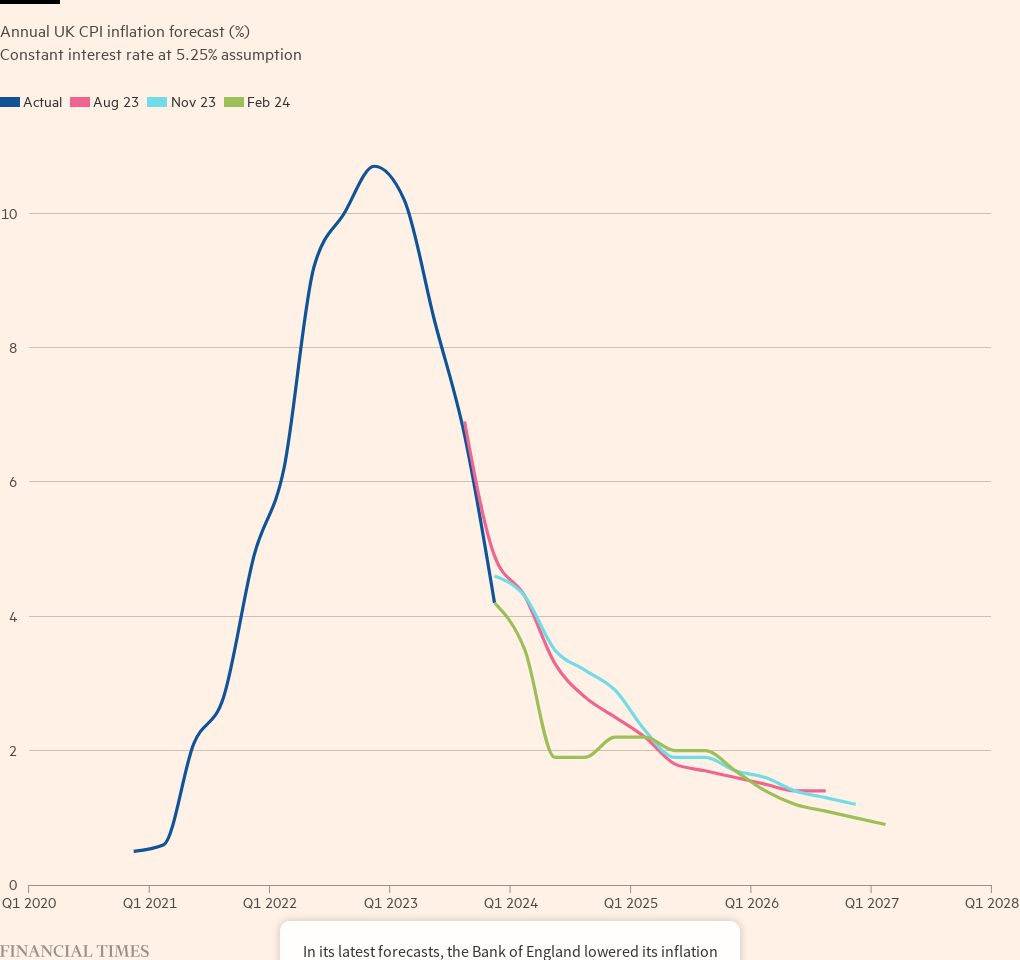

I received quite a lot of odd commentary from economists after the meeting suggested the BoE remains hawkish (because the inflation forecast was a little over 2 per cent on the main BoE forecasts). A better way of looking at the evolution of the Bank’s view is to look at how the inflation forecasts have changed based on the assumption that interest rates remain constant at 5.25 per cent. In the interactive chart below, you can also see the lower price level the BoE now expects. It shows the central bank is now much less worried about inflation. This was a dovish pivot.

Andrew Bailey got close to validating market forecasts for rate cuts by saying the Monetary Policy Committee just wanted more evidence of good inflationary news before it would cut. That could come by May or June. The governor certainly did not try to tell markets they were getting too excited and the lack of movement in the forward interest rate curve after the meeting pleased officials. The February meeting was not an attempt to influence market pricing.

The most interesting vote on the MPC came from external member Swati Dhingra, who voted for an immediate easing of policy seeking a quarter point cut from 5.25 per cent to 5 per cent. I caught up with her after the meeting and the following is a transcript of our conversation, edited for clarity and brevity.

Why did you vote to cut rates?

Swati Dhingra: The amount of time it took to get rates up was long, and couple that with the transmission lags and we’re basically still looking at a pretty restrictive period of monetary policy even after you start the moderation.

The data points that was important for me is that it’s now almost six months since we’ve seen consumer price inflation turn and in a pretty firm way. If you look not just at the mean CPI inflation, but the median as well, you see a very similar pattern. If you break down even further the 85 items in the index and look at all the 105 producer price index items and you look at what happened to [the annual inflation rate] at the turning point, CPI pretty much lags behind PPI by six or seven months. So I was fairly convinced that this wasn’t just energy driving everything. At this point about 97 per cent [of annual CPI inflation items] have turned down.

In December, you voted for rates to stay at 5.25 per cent. So what’s changed?

SD: Compared with December, we were hearing from the [regional] agents that people are saving up for the special treat for the festive season. So I was waiting for information and if we had seen a really sharp increase in retail sales or some kind of sharp increase in consumer prices, particularly on services. The fall in retail sales is pretty convincing. If anything, I think it was a bit unexpected. So I’m not fully convinced there’s some kind of really sharp excess demand in the economy coming from the consumption side.

Many on the MPC are concerned about services prices being sticky. How do you see this element of inflation?

SD: There is no denying that sharp improvement in the services price inflation numbers is lacking. But if you look at all the items — goods and services — the [annual inflation] numbers are looking very close to where they were in 2017 to 2019 averages. If you look at services inflation, the renormalisation has started, but we’re not at 2017 to 2019 averages. So there is some way to go. I think some of the arguments need to be made more symmetrically. We knew that services inflation would be slower to react on the way up and it’s going to happen on the way down too, in my view. I remember when I had just joined the MPC there was a very sharp increase in the restaurant catering services prices.

That being said, this is one place where I had to make a judgment call that at some point you’re going to see the turning point [in services inflation]. I think broadly, the goods price deflation is going to be big enough that the services price inflation, even with some stickiness, is just about enough to get back to target inflation.

What about wages?

SD: If you look at the numbers on wage growth now they still look like they’re high; if you look at the numbers later on in the forecast, they look lower. But I’m not going to advocate what wage growth should be because if you do go back to the pre-global financial crisis era when interest rates were pretty high, we had subdued inflation and we still had wage growth of some 4 to 5 per cent. So it’s not out of line with the history.

What do you see are the risks of not cutting rates?

SD: You’re asking me what would the counterfactual look like? I think most of us can agree, broadly, that policy tightening has had an impact on growth. I find it striking that even though we are seeing higher-than-historic rates of wage growth, the consumption numbers look so weak, with a 5.9 per cent drop relative to pre-pandemic levels. That fall in consumption is going to stay and that’s where the lagged effects of monetary policy tightening are still to come. I don’t see a reason to trade off weak consumption when we know that inflation is on a sustainable path at this point.

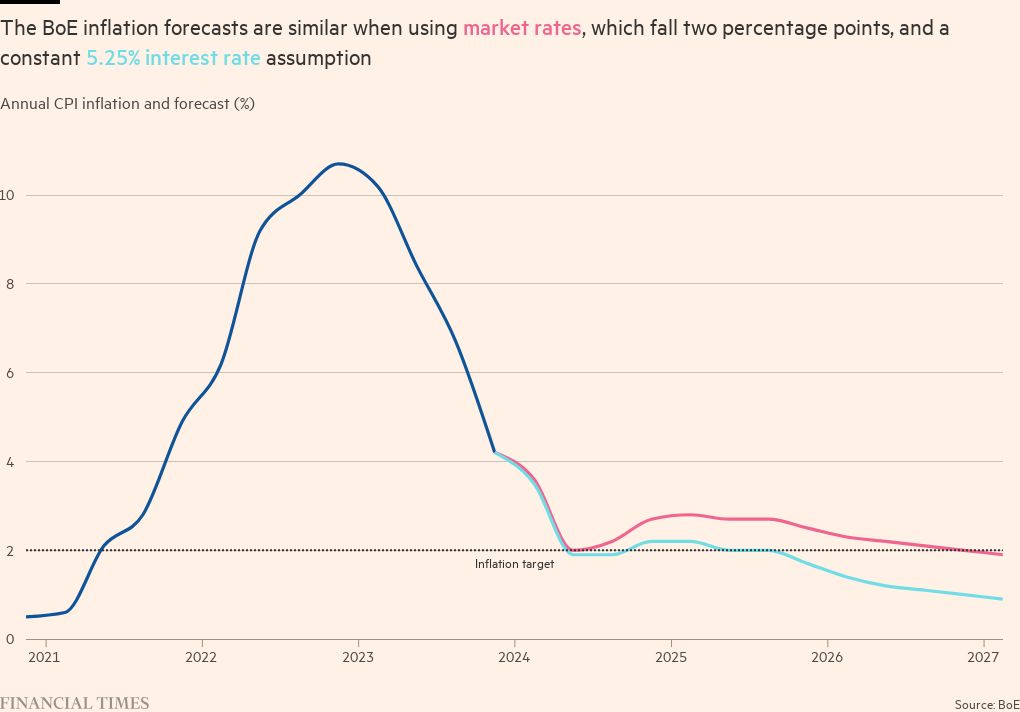

The BoE’s forecasts are interesting. It produces two, one with constant interest rates at 5.25 per cent and one using the market path which sees rates fall two percentage points in just over two years. The difference in inflation outcomes from this large difference in monetary policy is small. Do you think the BoE’s models are underestimating the power of monetary policy?

SD: When you look at the constant-rate forecasts and compare them with the ones conditioned on the market path, sometimes the difference in monetary policy would be pretty big, but the inflation that you would get would be pretty small. But if you compare what [the different interest rate paths] do to economic activity, it is actually quite big.

To the extent that economic activity may not be a primary goal, but is a secondary goal of the MPC, why would you want to sacrifice any growth if you’re not making a really big dent on inflation?

Ben Broadbent, deputy governor, gave a speech where he talked about our lack of knowledge and that was an argument to wait before cutting rates. Why have you taken a different view?

SD: I think that’s an OK argument. I find it sort of plausible that maybe what we’ve learnt from the last two years of inflation and particularly domestic inflationary pressures is that we have more to learn. And if tomorrow my assessment right now is not accurate, then maybe we should have waited. But I don’t necessarily buy the argument that you need to wait simply because cutting now sends the wrong message or a policy reversal is a bad thing. There are arguments on both sides. And my argument on the other side would be that with the kind of consumption weakness that we’re seeing it’s sort of hard to imagine how that’s going to get reversed so sharply that you will see a resurgence of inflation.

The second bit is that at some point we [have to ask what more] we have to learn. We have learnt, and we didn’t see the wage price spiral that most people were concerned about. We also don’t see profiteering from companies.

I’m more concerned that we might be underplaying the downside risks, particularly as we’ve been lucky to have the buffer from the pandemic savings to tide people over. That’s waning now. And job vacancies have really dropped. So, you might actually see that the real economy starts to get negatively hit in a more profound way. I don’t see why we should be risking that.

Is reversing course on interest rates if you cut too early the worst thing that central banks can do?

SD: OK, there might be some kind of financial market psychology, but I still think that if you do the right policy and if you even deviate for the right reasons, people understand. So I’m not that worried about it. There’s the second argument, which is now you’ve got to stay the course because, at least from the historical evidence, it looks like [the times policy did that] it resolved high inflation.

But if you look at the UK in the late 1970s and early 80s, monetary policy stayed tight that’s true, but gross domestic product really sharply contracted and unemployment went up from 5 to 12 per cent. It’s not till the 1990s that you see a trough to 6.9 per cent. This is not a soft landing. I mean, we’re in a very different situation right now. So why do we want to ever take that risk that we end up in that situation? I don’t find the evidence particularly compelling.

You have a reputation as a dove. Is this a correct characterisation?

SD: I’ve always found that sort of labelling strange. But yes, I voted always much lower than most of the people on the MPC. I think there were reasons to be worried about inflation. We haven’t seen this kind of inflationary pressure in the history of the MPC. So there were reasons to be cautious and there were reasons to put up rates, particularly given where they were at very, very minimal level. So I think that was a reasonable thing to do.

But where I differ from the committee was, I think a more moderate path of rate changes would be better, it’s easier to adjust from that. Otherwise, we’re going to have to make bigger adjustments.

From your experience, what is the most effective way of persuading the committee to vote with you?

SD: I don’t come from a monetary policy world and I had to learn very quickly in the first two or three months how the central banking world works. There’s much more volatility in the data than most of us who look at longer horizons see. That was one lesson. The second was if you want to convince people, you better have really sound evidence to back it up.

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

For a round-up of recent global monetary policy, my FT colleagues have produced this comprehensive big read

-

We produced lots of great US coverage this week. Also watch Jay Powell on 60 Minutes here where he says a March rate cut is unlikely unless the economy tanks. His press conference is here

-

Of course, someone is always unhappy. This time it is Donald Trump saying he would replace Powell (who he appointed). Quelle surprise

-

For an in-depth look at central bank losses over at the FT specialist site, go to Banking Risk & Regulation. This link gets you special access

-

Martin Sandbu claims victory for team transitory. It is thought-provoking. He likes the inflationary outcome, but in my view does not credit monetary policy sufficiently

A chart that matters

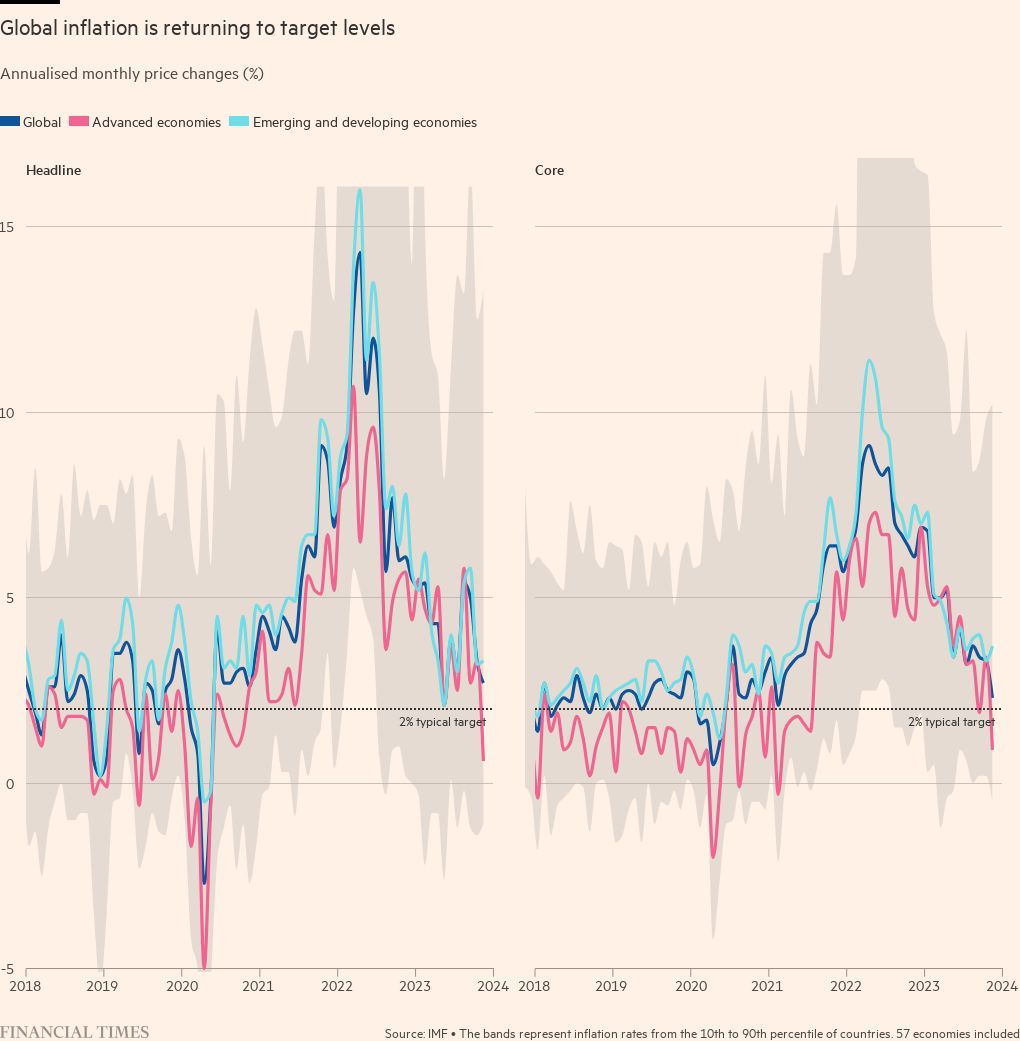

In one part of our interview Dhingra said she didn’t much like looking at monthly inflation numbers because they were so volatile. She is right about that. But the IMF has come up with a lovely global chart using the data averaged over 57 countries to smooth the results. The data accounts for 78 per cent of global output and is one of the most strikingly simple and effective descriptions of global disinflation trends in both headline and core that I have seen.