Don’t worry if you have, you’re not alone. What’s happened here is called self-serving or self-attribution bias. When things go well, people tend to think it’s their own doing, whereas when things go wrong, it’s someone or something else’s fault.

Company CEOs do it all the time. For instance, if the company does well, the CEO calls out their great decisions, tireless efforts, and development of a winning corporate culture. Yet if the company has a bad year, we read of external factors, such as commodity cost pressures, exchange rate headwinds, subdued consumer confidence, or government decisions impacting negatively.

Self-serving bias starts early on, though. In schools, how often do you hear about good grades coming from intelligence and hard work, versus bad grades being due to the test being unfair or a person feeling under the weather, and so on? Sometimes, your performance in exams is a case of luck: happily, your revision efforts overlapped well with the content of an exam paper that could have asked you a bunch of stuff you didn’t know!

One of Many Biases

The study of how psychological biases affect decision-making has become trendy in recent decades. Thanks in part to Nobel Prize winning Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, it’s extended to financial decision-making too.

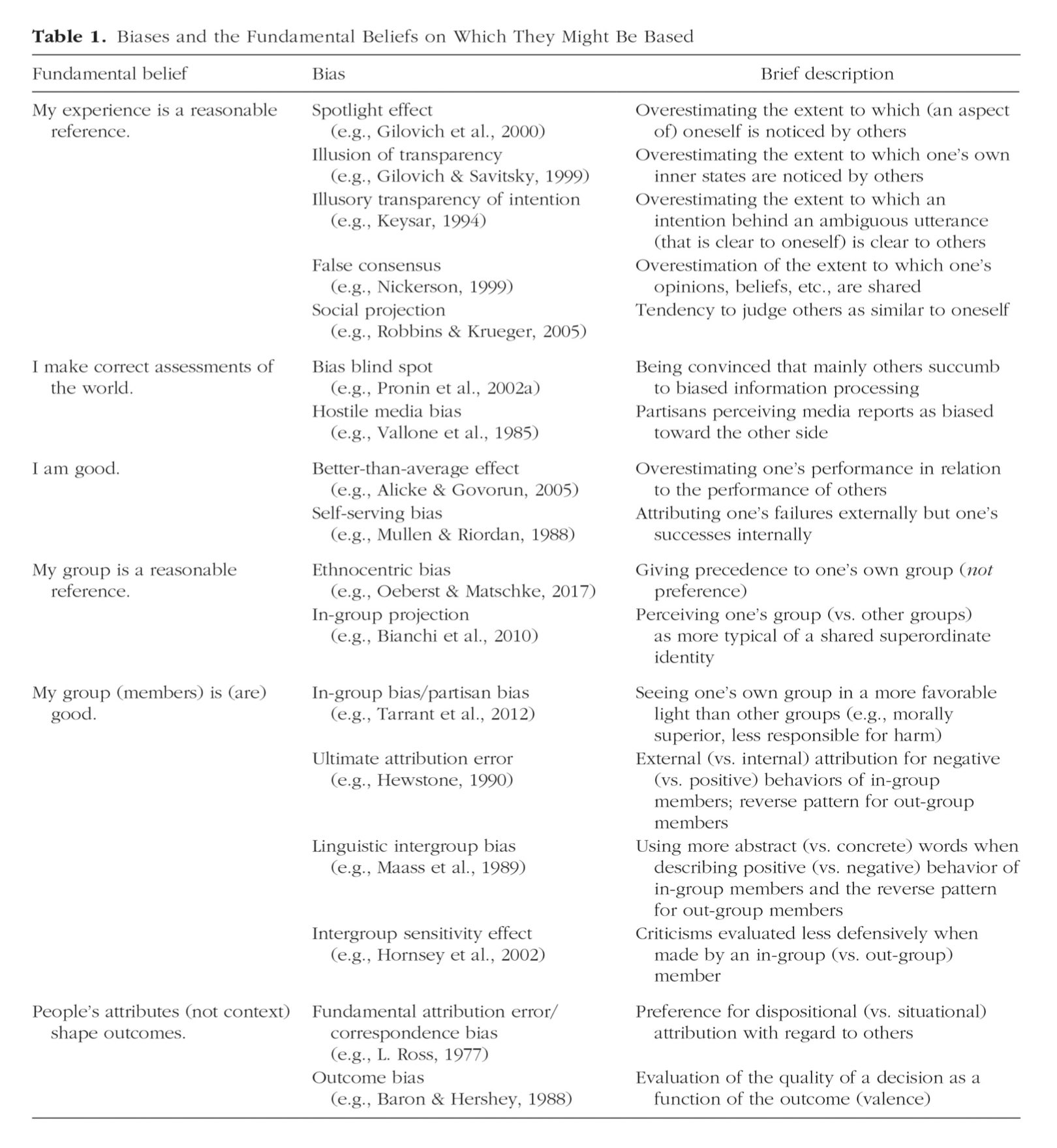

Psychologists have posited hundreds of cognitive biases over the years, yet a recent academic paper narrowed them down to just a handful of fundamental beliefs, coupled with so-called confirmation bias (we filter in things that confirm our existing beliefs, and filter out information that contradicts these beliefs).

You may have noticed self-serving bias under the “I am good” bias in the diagram. It turns out CEOs, school kids, and individual investors aren’t the only ones who display this bias, as fund managers do too.

Winning is Skill, Losing is Bad Luck

Academic Meng Wang has released research this month titled, Heads I Win, Tails It’s Chance: Mutual Fund Performance Self-Attribution. Fascinatingly, Wang used artificial intelligence and Chat GPT to analyse mutual fund shareholder reports from 2006 to 2018, including 15,434 shareholder reports from 1,969 separate funds.

In these reports, fund managers usually highlight what contributed to or detracted from fund performance as well as factors behind them. The comments may include internal factors, such as stock selection, sector weighting, and deviation from the benchmark. And they can also include external factors like the economic environment, conditions in specific sectors, and common exposure with the benchmark.

For example, Wang says: “the statement ;the fund experienced a positive contribution from its overweight exposure in industrials, which we attribute to the effects of individual stock selection’ implies an internal factor, suggesting the fund’s stock selection was a key contributor to its performance.” Conversely, “the statement ‘during the last six months, this was an impediment to the performance of the funds, as value stock returns have continued to outpace growth returns’ suggests an external detractor.”

Here are the main findings of the report:

- Astonishingly, on average, 59% of the factors attributed to performance contributors were internal while 41% of the factors were external;

- On the other hand, 83% of the factors attributed to performance detractors were external, and 17% were internal;

- Fund managers displayed significant self-attribution bias: they were 40.6% more likely to attribute performance contributors versus performance detractors to internal factors;

- Funds displaying greater self-serving bias were involved in greater risk-taking and tended to engage in excessive trading in the subsequent reporting period. This negatively impacted their performance and increased the fund’s volatility;

- A one standard-deviation increase in self-attribution score resulted in a 0.8% decrease in cumulative performance over the subsequent reporting period;

- Mutual funds had a higher self-attribution bias after better performance.

The psychological literature suggests the perception of self-attribution bias in others can elicit negative reactions, including frustration and dissatisfaction, and this study backs that up. It found fund flows overall were negatively affected by self-attribution bias.

In sum, fund managers put better performance down to their skill, and blame poor performance on bad luck;

James Gruber is an assistant editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.com.au